A long-year family friend at Frankfurt and a cousin at Bonn are both in their eighties. I want to visit them on my way to Berlin, mid-November 2021.

My first stop is at Frankfurt, the business capital of Germany on the Main river.

At Frankfurt, I have been invited by Dietrich and his wife. Our grand-parents were friends, after that our mothers were very close friends and now we, the grand-children, are friends. We are long-year family friends.

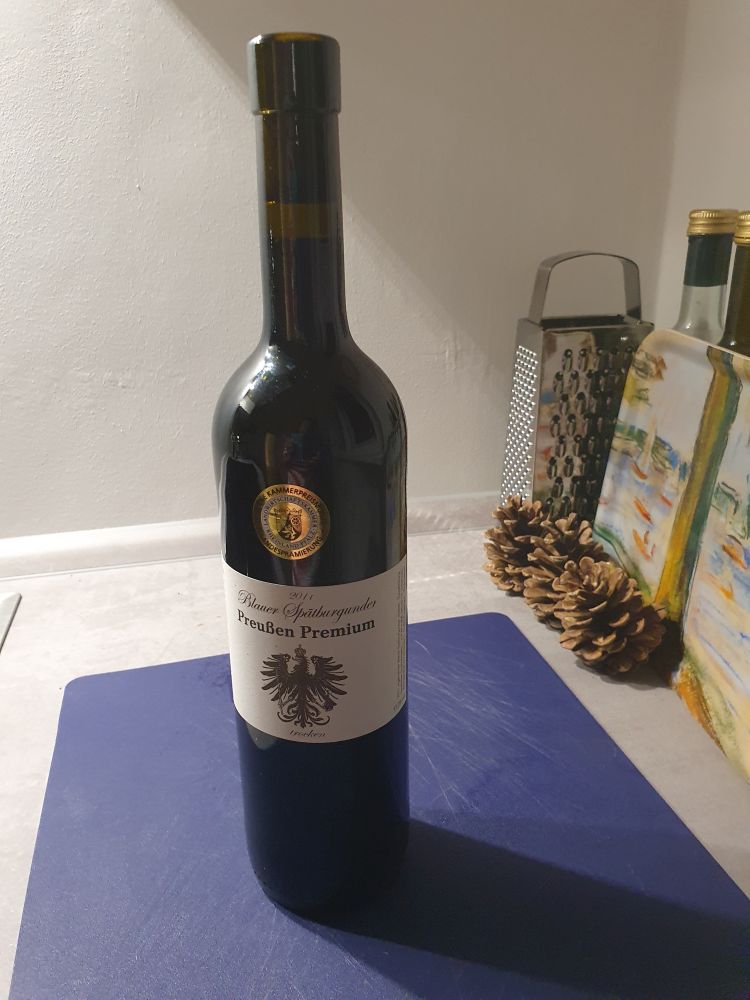

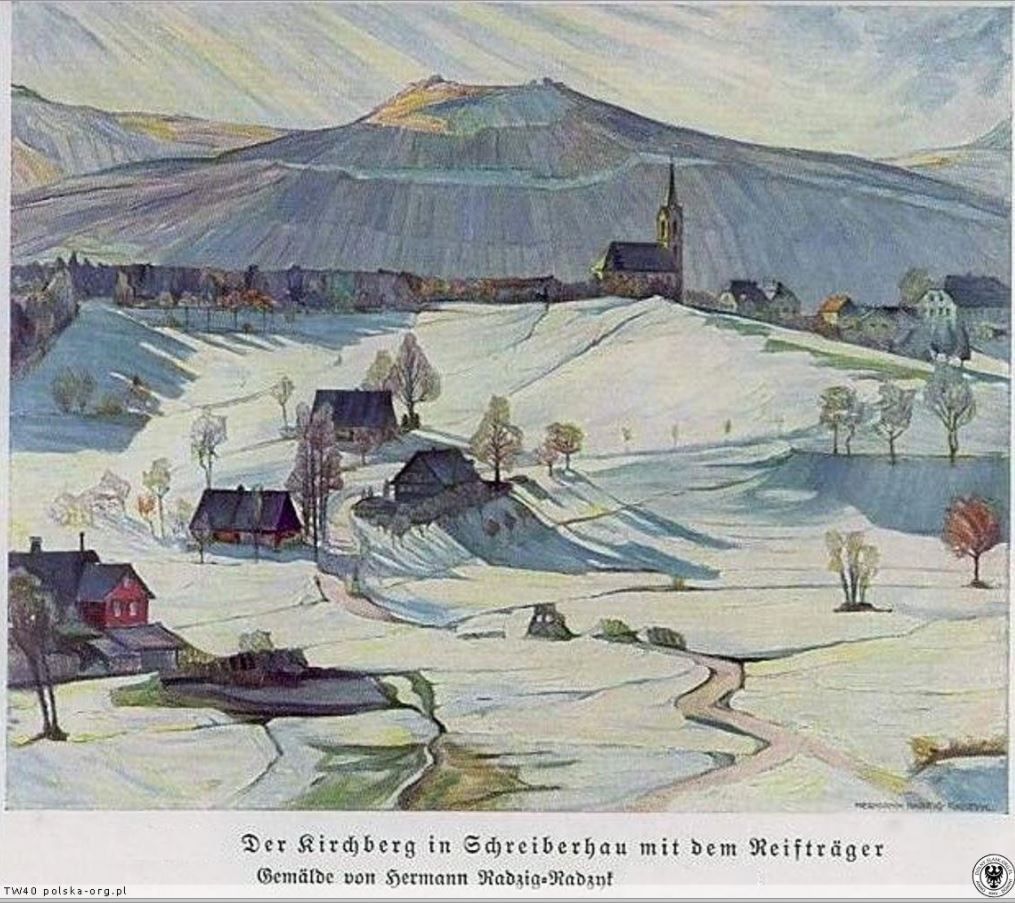

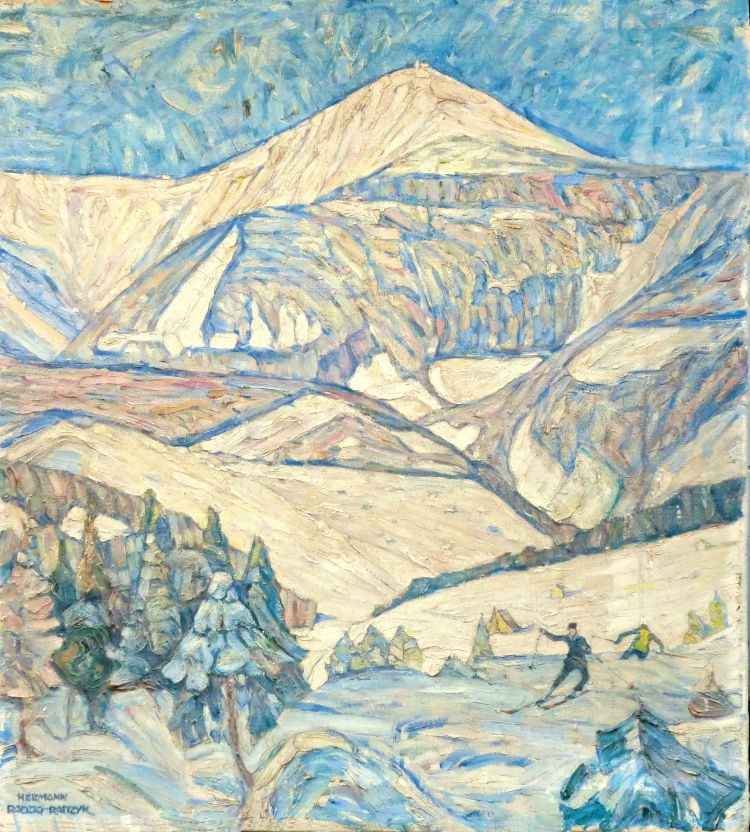

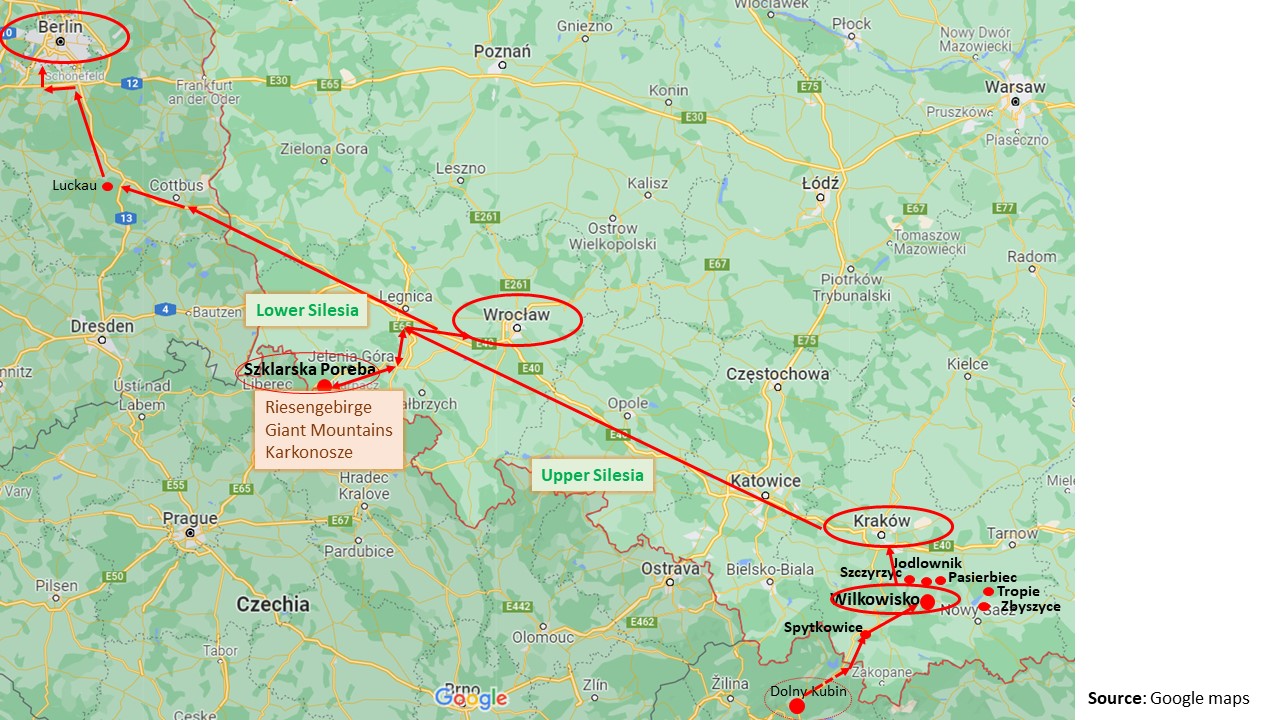

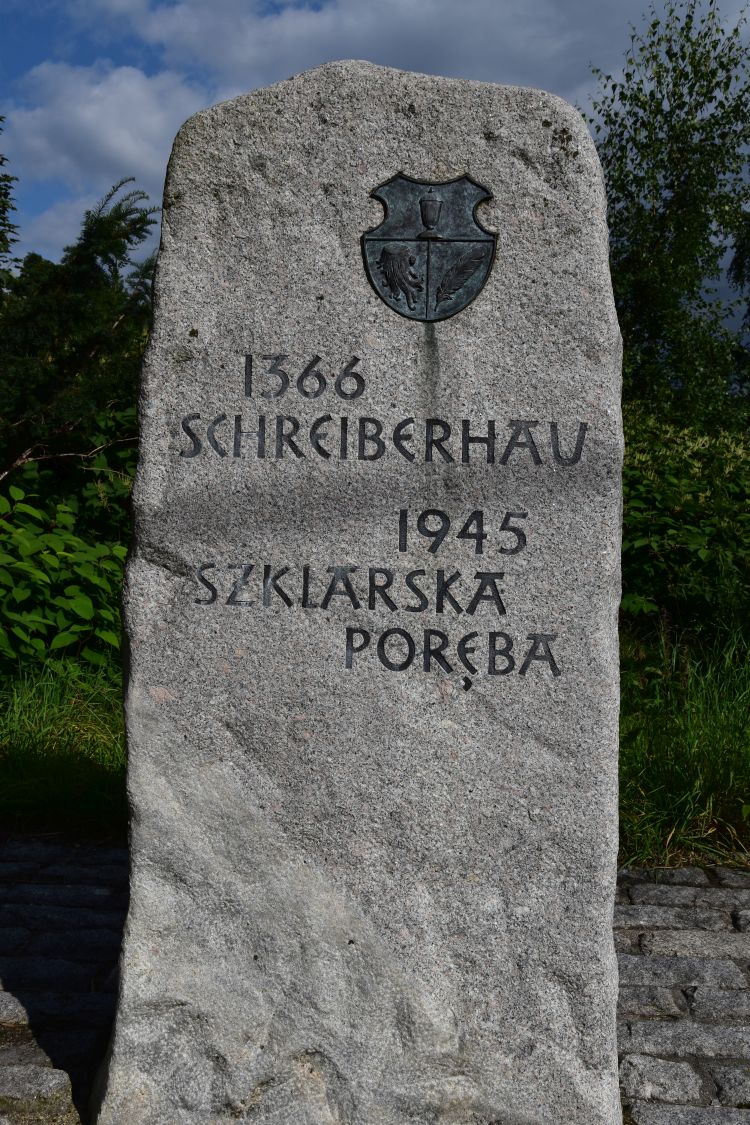

A hundred years ago, Dietrich’s grand-father had acquired some paintings of my grand-father-artist Hermann Radzig-Radzyk, for instance the Kirchberg at Schreiberhau, now Szklarska Poręba, in Silesia…

… and the valley at the county of Kłodsko (Glätzisches Land), also in Silesia.

Immediately, I feel at home in the house of Dietrich and his wife. I am surrounded by memories of my family, and the welcome is hearty.

Charming small Italian restaurant run by two sisters from Naples

We have dinner at the charming small Pizzeria La Paesana, run by two sisters from Naples. Their nephew made the pretty felt pizzaiolo that now decorates the pizzeria of his aunts. Well, the pizzaiolo has lost one eye – that makes him look even friendlier – he seems to twinkle at me.

The small restaurant is an excellent welcome to Frankfurt. I have tasty wild boar noodles with a slightly sparkling Lambrusco, my friends have pasta Carlo Magno with Gorgonzola – it is said that Charlemagne (Karl der Grosse or Carlo Magno) loved Gorgonzola, the sisters tell us. That was around the year 800 AD – what a cheese tradition!

(According to the wiki entry about Gorgonzola, it is said that Gorgonzola was first produced in 879; but this could well have happened a little earlier, when Charlemagne lived, and if not, it is a nice legend).

We will meet Charlemagne later again in the city centre of Frankfurt.

My first impression of the city – Hauptwache (main guardroom) and skyscrapers touching the morning clouds

Dietrich takes me to the S-Bahn. We leave the underground station at the Hauptwache (main guardroom). Saint Catherine’s Church appears behind the stairs.

The baroque guardroom, built in 1730, was the headquarter of the city’s soldiers. It was also a prison. It was destroyed in the Second World War and reconstructed thereafter.

The Hauptwache is surrounded by modern buildings, with the Commerzbank building fading in the mist of the late morning.

The lifeline of Frankfurt am Main – the river Main

The lifeline of Frankfurt is the Main river. We approach it near the pedestrian bridge “Eiserner Steg” with the inscription in Greek saying “the sea has the colour of wine and, on this sea, we are sailing to meet other people” (auf weinfarbenem Meer segelnd zu anderen Menschen).

From here we can see the Commerzbank building again, now under blue sky in the sun, surrounded by many more modern buildings reflecting in the Main river .

This is the Cathedral Saint Bartholomew, also reflecting in the Main river.

Across the Eiserner Steg we reach the urban district Sachsenhausen. We stroll along the waterside promenade and meet these two ducks, also citizens of Frankfurt, sleeping comfortably on one leg.

The skyline, again with the Commerzbank tower, appears behind the island (Maininsel) that shines in golden autumn colours.

Returning to the city centre using the Old Bridge (Alte Brücke), I make a photo of both the modern business skyline and the Gothic Cathedral of Saint Barthomolew.

Frankfurt has charm, definitively, when seen from their lifeline, the Main river.

Timbered houses at the Römerberg and the Old St Nicholas Church (Alte Nikolaikirche)

Away from the Main river, the old city centre is located on the Römerberg. It is bordered by timbered houses and the Old St Nicholas Church.

We enter the Römerberg square under the banner that plays with German words: “Vieles geht besser, wenn die Maske jetzt sitzt” (translated literally: “much will “go” better, when the mask “sits” meaning”, when the mask fits – it is the times of COVID).

On the Römerberg, the first fairs took place in the 11th century. Frederic the Second of Hohenstaufen granted the right to run fairs to Frankfurt in 1240.

It is mid November, time to set up the Christmas tree in front of the old town hall.

This is not the Standesamt (civil registry office), but the Standesämtchen. The ending “chen” combined with “ä” indicates that it is the “small” registry office which, in Southern Germany, adds a friendly and welcoming touch to it. Actually it is not a small civil registry office, but a restaurant that carries the name “Standesämtchen”.

Modernity and tradition are joining. The Old St Nicholas Church reflects in the glass wall of the Evangelische Akademie (education institution and conference house).

As a matter of fact, Frankfurt has been in ruins after the Second World War. The houses around the Römerberg, originally from the 15/16th century, have been reconstructed in the 80-ies, except the Wertheim building nearby that survived the air raids.

The late Gothic Old Saint Nicholas Church from the 15th century only suffered minor damage by the bombs of the Second World War.

The Cathedral St Barthomolew behind the Römer

From the Römerberg, we can see the Cathedral of St Barthomolew.

The cathedral can be seen from the Main river, too.

The cathedral is also called “Kaiserdom” (Emperor Cathedral). Actually, it is a “Königsdom”, because the kings of the Holy Roman Empire were elected here since 1152 and crowned since 1562, until the Holy Roman Empire ceased to exist. No “emperors” were crowned here, kings were crowned here. Furthermore, the cathedral has never been a bishop seat, though it is called “cathedral”.

The present Gothic cathedral is mainly from the 14th and 15th century, reconstructed in the 1950’s after having been severely damaged in 1944.

The modern organ matches the gothic vaults.

Reading about the cathedral at home, I would like to return to explore the collection of altars from all over Germany and the chapel, where the elections of the kings took place.

New Old City (neue Altstadt), reconstructed based on the medieval ground plans

Between the Römerberg and the cathedral of St Bartholomew, the old city has been rebuilt along the medieval ground plans – this is now called “neue Altstadt” or “New Old City”.

The area is not without charm. However, to me, the houses look a bit, as if they had been cut out of cardboard.

They are neither really old nor really modern.

Kaiserpfalz – meeting Charlemagne again, the emperor who enjoyed the Gorgonzola cheese

Here, he is again, Charlemagne who is said to have loved the Gorgonzola cheese. In a way, he is the founder of Frankfurt. That is why, I assume, he stands on the old bridge crossing the Main river. He looks downstream, severely frowning.

In 794, it was Charlemagne who was the first person to mention Frankfurt or “Franconofurd”. At that time, he held a synod of bishops and an imperial assembly here.

Charlemagne was at Frankfurt in 794. However, later he probably never returned to Frankfurt. It is assumed that his grand-son, Louis the German, founded the first cathedral and made Frankfurt an important royal palatinate. The ruins of the palatinate are presented in the New Old City.

This is, what the royal palatinate (Königspfalz) might have looked like in the 9th century.

The painting is on display in the museum.

Church St. Leonhard

The Church St Leonhard is bordering the Main river. The beginnings go back to the early 13th century, and the Romanesque structures have been largely preserved. In 1323, the church acquired a relic of Saint Leonhard which made it an important pilgrimage site.

In the early 15th century, the choir was reconstructed in Gothic style while the Romanesque apses remained in place. Around 1500, the nave was enlarged.

The Gothic main altar was acquired around 1850. The middle part is from Swabian Bavaria. The predella is supposed to have been crafted at Memmingen in the late 15th century; it shows the martyrium of Ursula. The two candle holders are Baroque angels from 1614.

Late Gothic frescoes decorate the walls of the choir, to the left the Annunciation scene, to the right Christ carrying the cross. Some of the stain glass windows in the choir are from the 15th century.

The altar of Marie comes from Antwerpen (about 1480). The centre part is dedicated to Marie (her death, her ascension, her coronation). The predella shows the Last Supper.

In 1944, the Church Saint Nicholas was only moderately damaged; sister Margarita prevented a devastating fire. Between 2011 and 2019 the church was completely renovated.

Reading the booklet acquired in the Church of St. Nicholas, I understand, there is more to see in this church, I would like to come back.

Goethe was born at Frankfurt

In this large, yellow house at the Grosser Hirschgraben, Goethe was born (1749-1832) . He lived in Frankfurt, until he left to study law at Leipzig in 1765.

Well, the yellow house was destroyed in 1944, and it was reconstructed after the war, exactly as it was before.

Next door is the Frankfurter Goethehaus (House of Goethe) with the Deutsches Romantikmuseum (German museum of Romanticism). I liked the highly modern oriel interpretation.

Again next door is the Volksbühne, a theatre, with two more modern oriels swinging along the façade.

Town Hall and Local Court (Ortsgericht)

From the Goethe House we cross the busy Berlinerstrasse and reach the Local Court of Frankfurt (Ortsgericht), …

… leaving it through the gate with the fresco showing the wine harvest.

We now look at the rear side of the town hall, …

… with the town hall tower seen from under the Seufzerbrücke (Bridge of Sighs, a skywalk) at Bethmannstrasse.

St Paul’s Church (Paulskirche)

Behind us, we can see the oval shaped classicist Saint Paul’s Church, completed in 1833. In 1848, the first German national assembly was held in Saint Paul’s Church. However, the attempt to found the German nation failed, as the Prussian king did not accept the emperor crown to reign over all German states. Nevertheless, the constitution elaborated by the assembly was accepted by most German states; it can be considered to be the roots of the German democracy (see Stadtführer, p. 38).

The building was reconstructed after 1945 to become a national memorial. This is the new cupola seen from inside.

A monumental frieze makes the representatives of the 1848 assembly revive.

Sight seeing makes hungry – the Kleinmarkthalle (small market hall) is close

Around lunch time, I am usually hungry. We make a “pitch stop” at the Kleinmarkthalle (small market hall) near the city centre.

We climb up the stairs to get an overview from the gallery.

We walk around and enjoy the stands with enticing pasta,…

… apple wine (called Ebbelwei here), …

… meat offered by a citizen of Frankfurt that is obviously from Turkish origin (I love to see the mixture of nations here),…

… beautifully arranged fish… and much more.

We join the waiting queue at Dietrich’s favourite sausage stand of Ilse Schreiber, where we buy two sausages from Hessen (the state that Frankfurt belongs to). We have to eat our sausages outside, because inside the building we have to wear masks, outside, we can take them off, which is much more convenient for eating sausages.

Good-bye Dietrich, now I am heading north to Bonn, with a stop over on the Grosser Feldberg

Thank you, Dietrich, I have spent two wonderful days with you and your wife. I have learnt much about Frankfurt, and there is more to see in Frankfurt with its museums, with the modern business centres, with the carefully preserved or reconstructed medieval sights and with its lifeline, the Main river.

Now I am heading north to Bonn.

In the mist, I start driving to the Taunus mountains north of Frankfurt. My car climbs and climbs, and eventually, I am above the clouds. I stop on the local mountain of Frankfurt that is called Grosser Feldberg. I am on almost 900m. The view is superb.

The Brunhildi’s rock (to the right of my shadow) is mentioned in a document of 1043.

The rock is said to have been the “lectulus of Brunhilde” or “the little bed of Brunhilde”. Saint Hildegard of Bingen has spent one night here, and the rock has kept the imprint of her head, as legends tell. Around 1800, the rock was reinterpreted as the place, where Brunhilde was sleeping, until Siegfried liberated her. The rock became part of the German legend of Nibelungen. This is, what the panel near this peculiar rock says.

I continue north – it is about two hours to drive to Bonn. On the way, I will have another stop at Limburg.

Sources:

- Wikipedia entries for Königspfalz https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C3%B6nigspfalz_Frankfurt, for Frankfurt https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankfurt_am_Main#Von_der_Frankenfurt_bis_zum_Ende_des_Heiligen_R%C3%B6mischen_Reiches and for the Kaiserdom https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaiserdom_St._Bartholom%C3%A4us.

- Wolfgang Kotz, “Frankfurt, Stadtführer mit 101 Farbbildern”, Kraichgau Verlag, acquired in 2021.

- Matthias Theodor Kloft,”St. Leonhard, Frankfurt am Main,” Bistum Limberg, acquired 2021 in the church.

- Panel on the Grosser Feldberg near Frankfurt