End of August 2021, I am on the road again, to Berlin via Slovakia and Poland.

My route begins in Slovakia: Bratislava – Trnava – Nitra – Žilina – Strečno and Terchová – Dolny Kubin, Podbiel and Tvrdošín. It continues in Poland: Wilkowisko – Kraków – Szklarska Poręba – Wroclaw, and finally I am Berlin.

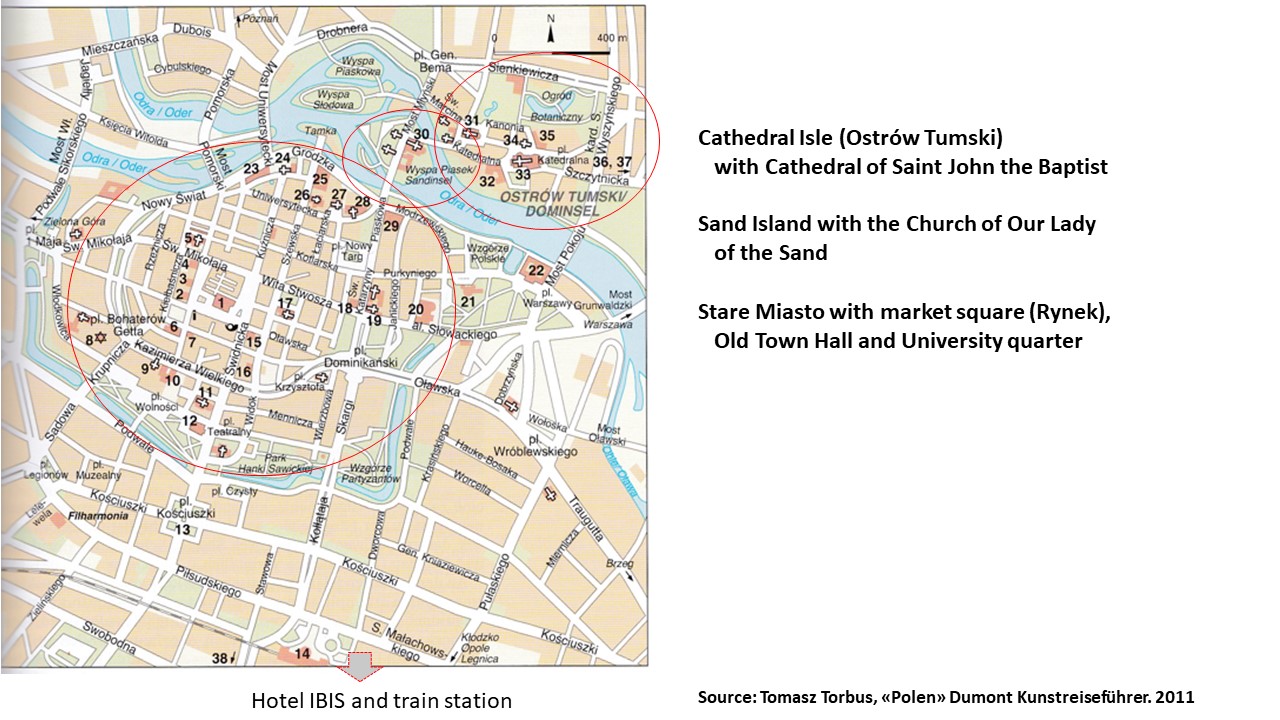

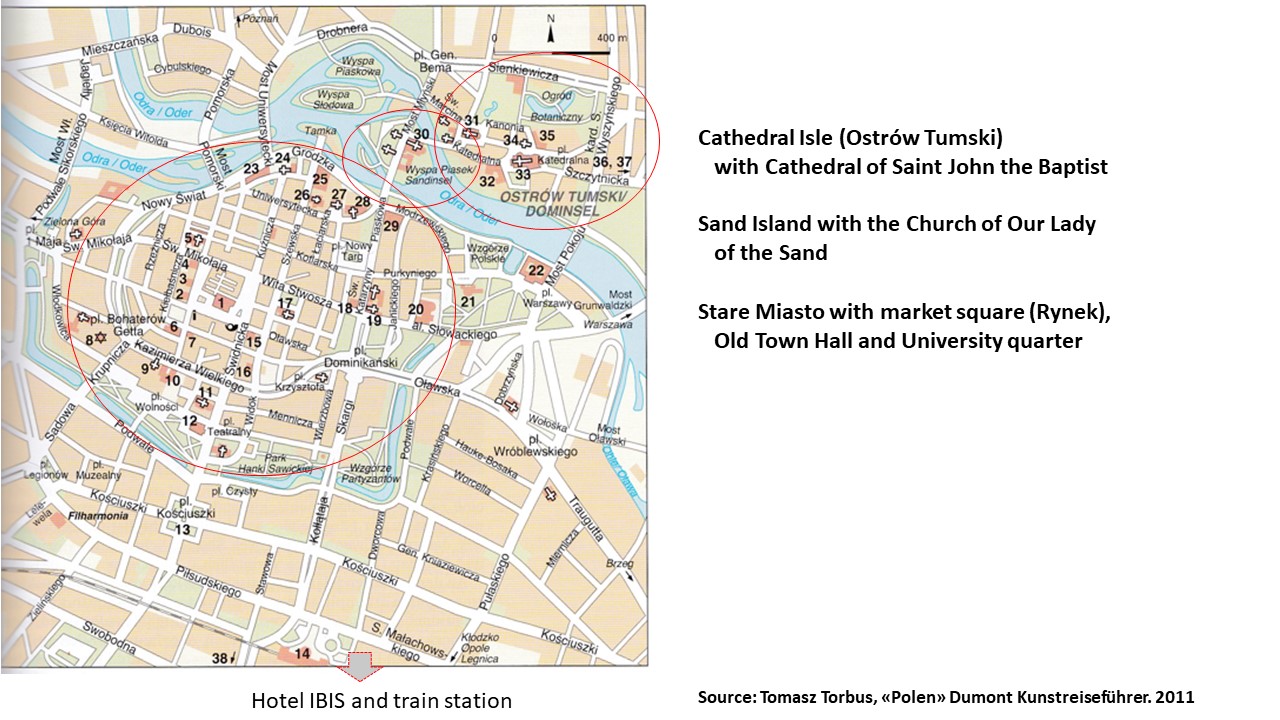

To round off my days in Poland, I stay one night in Wrocław (or in German Breslau).

I have selected the Hotel IBIS Styles Centrum. I look for a functioning hotel infrastructure and easy access to parking. Furthermore the IBIS is conveniently located, not too far from the city centre and across the train station. When getting lost, you can always find the train station in a city.

I am south of the city centre, about half an hour’s walk away from it.

Source: Tomasz Torbus, “Polen”, Dumont Kunst-Reiseführer 2011

The city centre of Wrocław stretches along the river Odra (Oder) and consists of three main areas:

- Stare Miasto with the market square (Rynek) and the Old Town Hall as well as the University quarter. Part of the moat has been preserved.

- The roots of the city are on Ostrów Tumski or Cathedral Isle with the cluster of churches (founded before 1000 AD).

- Sand Island lies between the city centre and Cathedral Isle.

I was all surprised to come across the river Oder here… I know it from the “Oderbruch”, the Oder wetlands in Brandenburg, at the border to Poland. But yes, the river Oder or Odra starts in the Czech Republic, flows through Silesia, makes the border between Poland and Germany for almost 200km and ends in the Baltic Sea.

Walking from the hotel to the city centre

From my hotel, I walk north towards the city centre. After some ten minutes, I reach the moat, the Fosa Miejskia on Ulica Podwale.

I like the pretty Art Nouveau houses along Ulica Podwale.

Now I am zooming in Atlas carrying not the world, but the oriel. It is so heavy that he has a brother and a sister helping him.

Stare Miasto with the Old Town Hall and the market square (Rynek)

I reach the Old Town Hall. The construction of the mainly Gothic building lasted from about 1300 until the middle of 16th century, adapting to changing needs over time. In 1930, the Old Town Hall was converted into a museum. Dumont rates it as one of the most beautiful profane buildings in Eastern Middle Europe (p. 246).

This is the eastern façade. The astronomical clock is from 1850.

Now we look at the west side of the Old Town Hall. I stand on the Rynek.

Humorous gnomes (or dwarfs) are scattered all over the city centre. There are more than 150 of them, as I read in my “old” Lonely Planet. I come across “my” first one near the Old Town Hall.

The gnomes can be considered to be an allusion to the Orange Alternative (Pomaranczowa Alternatywa), a group of communist dissidents in the 1980’s that used intelligent humour to express their political protest. Waldemar Fidrych was their leader.

In the narrow streets north of the Old Town Hall, I have delicious Spaghetti in a tiny Italian restaurant.

Since 1240, there has been a market square, where the Rynek is today. The Rynek is a charming mixture of Gothic and Art Nouveau houses. The north and south side had been destroyed in WW II. Everything has been reconstructed or renovated. It is Poland’s second largest Rynek after Kraków.

The Rynek is full of inviting restaurants.

I plan dinner at Fredro’s. Count Aleksander Fredro (1793-1876 ) was a noble landowner and a poet venerated in Poland. Dumont calls him the “Polish Molière” (p. 249).

Here are some of the colourful houses at the Rynek. The playful façade of the pharmacy attracts my attention.

Furthermore I like this house with the frescos. Dumont tells me that it is the house of the seven electors (Haus zu den sieben Kurfürsten), painted in Baroque style by Giacomo Scianzi (1672).

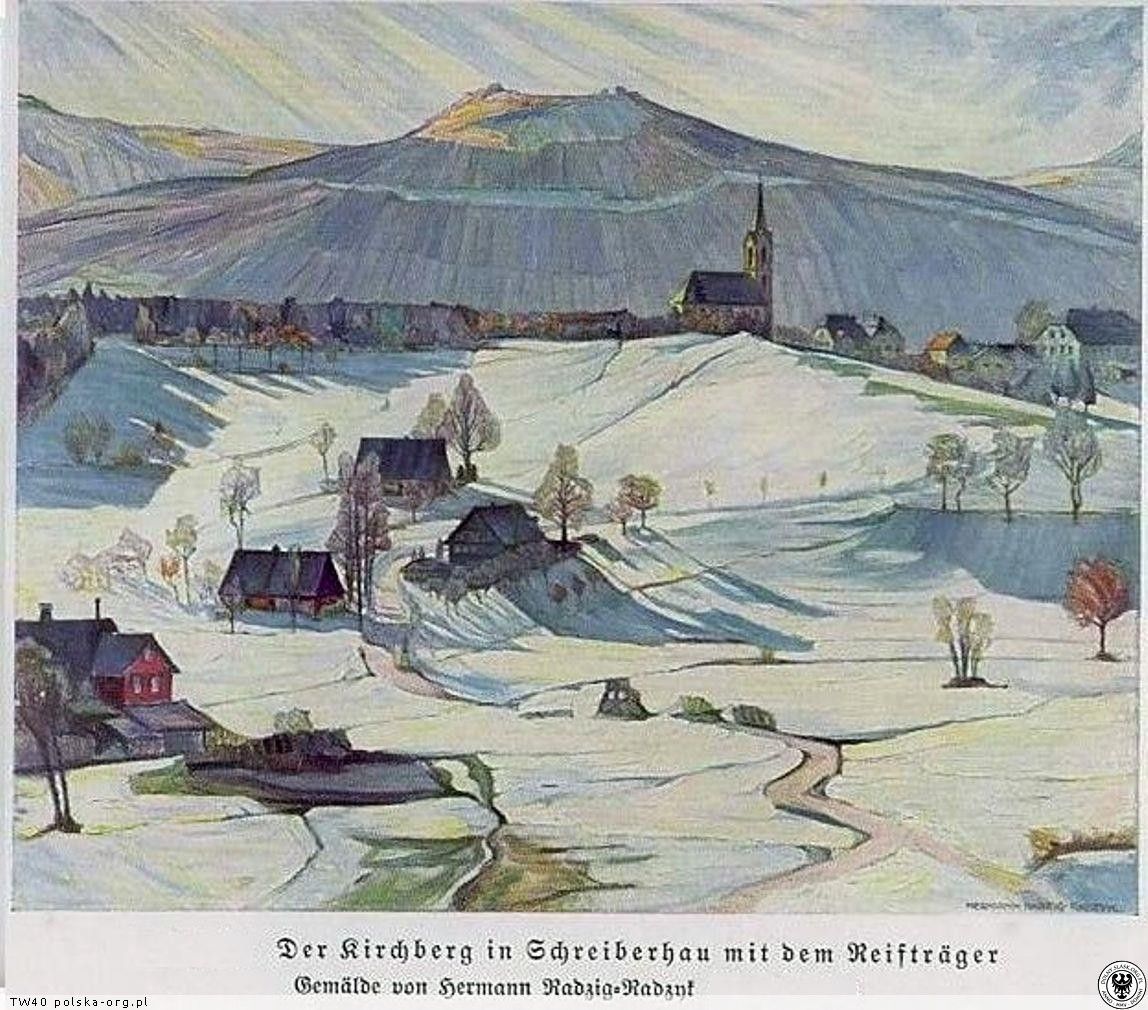

The glass wall in front of the New Town Hall symbolizes the Sudetes or Giant Mountains (Riesengebirge, Karkonosze).

Hänsel and Gretel is the name of these two tiny and slim houses. In Polish they are called “Jaś i Małgosia”.

The Church of Saint Elizabeth (Bazylika św. Elżbiety) is a Gothic brick building from the 14th century.

It was a Lutheran church from 1525 until 1946. Then it became a catholic church. It was heavily damaged by a fire in 1976 and has then been restored tastefully.

University Quarter

To the north of the Rynek, I find the university. The Habsburgian emperor, Leopold I, founded the university of Breslau in 1702 as a Jesuit academy. This was a catholic institution in mainly protestant Silesia and acted as a centre of the Counter-Reformation, until Silesia was conquered by the protestant Prussians in 1741. The university was re-established in 1945 replacing the former German University of Breslau.

This is the north view from the river bank.

This is the view from the south.

This professor-gnome-dwarf makes it very clear: This is a university!

The Baroque University Church of the Holy Name of Jesus (Kościół Uniwersytecki p.w. Najświętszego Imienia Jezus) was built by the Jesuits in the late 17th century. It reflects in the windows of the modern building across.

The market hall is an Art Nouveau building constructed in 1906-1908. It is in use as a product market until today.

Sand Island (Wyspa Piasek) with Church of our Lady on the Sand

To get to the Cathedral Island or Ostrów Tumski, I cross the small Sand Island or Wyspa Piasek.

The 14th century brick Gothic Church of our Lady of the Sand (Kościół Najświętszej Marii Panny na Piasku) is the dominating building on this small island.

This is the inside view with the Gothic vaults, 24m high.

The church has been destroyed during WW II. The tasteful stain glassed windows are modern, from 1968.

Cathedral Isle (Ostrów Tumski)

I approach the Cathedral Isle walking along the Odra or Oder. The two towers of the Cathedral Saint John the Baptist dominate the skyline.

I cross the Tumski bridge that in local legends tells love stories – similar to Romeo and Juliet. To the left is the Saint Peter and Paul church and in the background we see the towers of the Cathedral.

Another gnome-dwarf here.

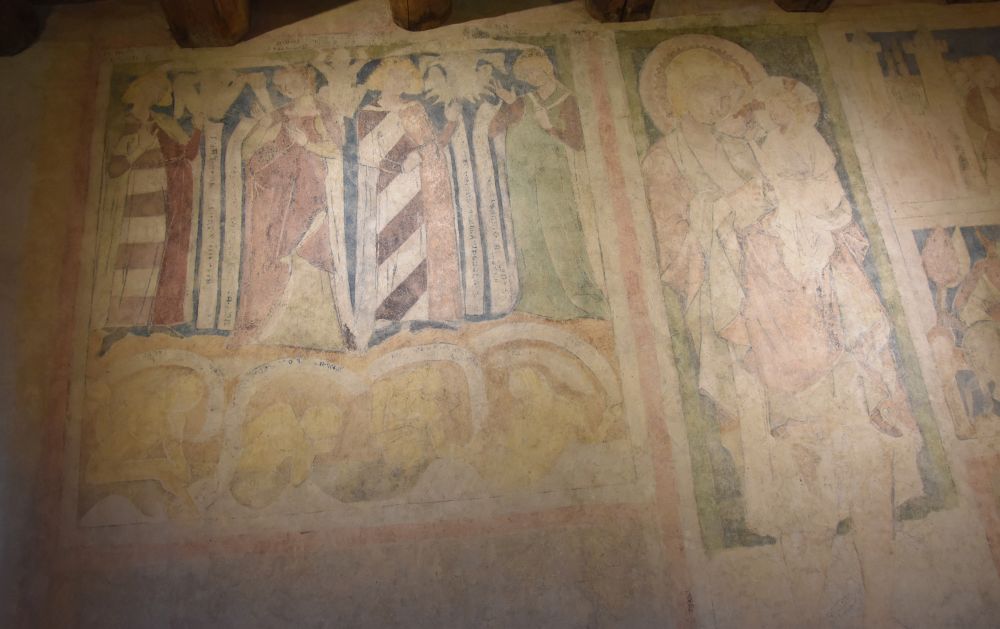

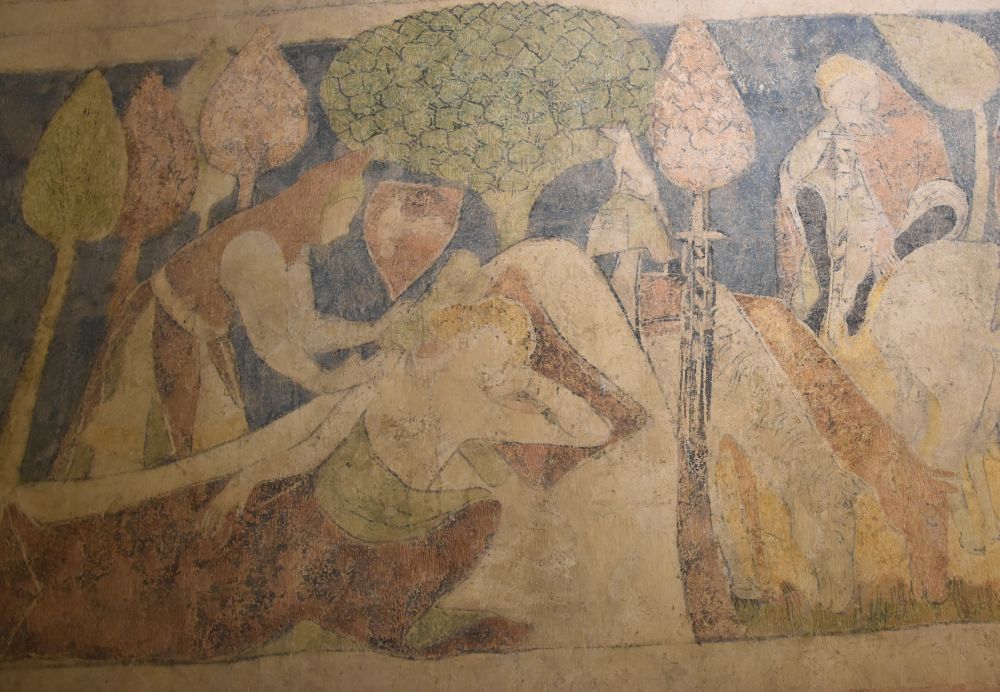

The Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross and St. Bartholomew (Kolegiata Świętego Krzyża i św. Bartłomieja) is a late Gothic brick church with two storeys.

The lower level is closed. I can look through a grill locking the door to get an idea of the upper level.

Elaborately cut trees lead to the Cathedral Saint John the Baptist. In Polish it is called Archikatedra św. Jana Chrzciciela.

The current construction in Brick Gothic was started in 1244, after the Mongolian invasion of 1241. Fires damaged the church in 1540 and in 1759. Then during WW II 70% of the cathedral were destroyed. It was reconstructed after WW II.

Across the street and north of the Cathedral is the small Church of St Giles (Kościół św. Idziego; in German: Aegidius). Built in Romanesque style in the early 13th century, it is the oldest active church in Wrocław. It has survived the Mongolian attacks.

Nearby Saint Martin Church is also of Romanesque or early Gothic style.

Coffee and Legends – taking a break in the Bishop’s Gardens

Behind the cathedral, I see this friendly invitation to the coffee place in the garden.

I enter and order a coffee. With it I receive a piece of paper, carefully rolled up with a bow. It contains legends of Ostrów Tumski.

While drinking my coffee, I read the legends referring to Ostrów Tumski.

One legend tells about the dangerous power of white roses. The bishop loved Agnieszka who cultivated white roses in the Bishop’s Gardens. When Agnieszka died, the servants wanted to comfort the bishop and decorated his bedroom with white roses. The following night, the bishop died. Since that night, white roses, now considered to be dangerous, have no longer been planted in the Bishop’s Gardens.

I leave the coffee place looking back at the Bishop’s Garden with the cathedral towers in the background,…

… and cross the bridge Tumski…

… that crosses the river Odra.

The White Stork Synagogue southwest of the Rynek

I return to the Rynek and continue my way southwest to visit the Jewish heritage, the White Stork Synagogue (Synagoga Pod Białym Bocianem), built in elegant neoclassical style in 1829 and restored in 2010. It is presumably called “White Stork”, because it stands where there was a restaurant with the same name before.

In the adjacent courtyard, I am tempted to sit down in one of the restaurants.

However, I return to the Rynek to eat in front of the Old Town Hall at Fredo’s. I have a salad with chicken and I complete my meal with a glass of Żubrówka, the Polish vodka with the buffalo grass.

Good-bye Wroclaw

Evening falls. I walk back to my hotel. I take Ul. Świdnicka (former Schweidnitzerstrasse) that in the 19th century became the new centre of the city with the Opera House from 1839-41…

… and department stores like this Art Nouveau building across the moat.

In the side streets, I come across German reminiscences.

I settle in “my” comfortable hotel IBIS. I have a glass of wine in the friendly restaurant here to say good-bye to Wrocław and also to Poland.

Tomorrow I will drive to Germany to my mother-town Berlin.

Background information about Wrocław and Silesia: The history in a nutshell

From the “Lonely Planet”, the “Dumont” and from various Internet sources about Silesia, Wrocław, the Piast family etc. I try to understand the major history pattern. I am not a historian, but I like to acquire a structured overview, though it may not be perfect.

Before 990: The roots of Silesia

- In the 4th/5th century, the Vandal tribe Silingi (in German: Silinger) settle, where Wrocław is today. In the 6th century the Slavic tribe Slegani build a fortification on Ostrów Tumski. It is under debate, which of the two tribes is the basis for the name “Silesia” (or in German: Schlesien, in Polish Śląsk).

- Until 985 today’s Silesia belongs to Bohemia.

985-1335: Under the rule of the Piast dynasty, first Polish and then more and more tending towards the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation

- 985: Duke Mieszko I. from the Piast family conquers Silesia with Wrocław and integrates it in the kingdom of Poland.

- 1000: For the first time, Wrocław is mentioned under the name of Vratislavia, in a Papal bulla. The diocese of Wrocław is one of the three newly founded Polish bishoprics. It is located, where two trade routes intersect. (In 2000, Wrocław will celebrate its 1000 years anniversary).

- 1241: The Mongolians (or Tartars) destroy Wrocław and retreat due to successor fights in Mongolia. Wrocław is rebuilt again.

- Late 13th century: Various branches of the Piast families reign their own duchies, one of them being Silesia. Poland is now a community of duchies with one duke being elected as the leader. The dukes of Silesia balance their politics between Poland and the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation. They invite Germans to settle. Soon the German colonists are a majority in Wrocław. In 1261, Wrocław takes over the town law of Magdeburg.

- 1335: The last member of the Silesian Piast family branch dies. The last Piast king of Poland, Cazimir III the Great, declares to abstain from Silesia; he prefers to focus on expanding the kingdom of Poland to the east.

1335-1526: Under Bohemian rule as part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation

- 1335, after the renunciation of the Polish king, Silesia and Wrocław are part of the Bohemian kingdom and hence part of the Holy Roman Empire of German Nation. Wrocław flourishes as a trade and handcraft centre.

- 1523 Silesia and Wrocław join the reformation, the leader is Johann Hess.

- 1526 With Ludwig II, the last member of the Bohemian-Jagellonian dynasty dies and the Habsburgians inherit Bohemia (they have married in, as usual).

1526-1741: Under Habsburgian Rule

- 1526: Having inherited Silesia, the Habsburgians fortify Wrocław to withstand modern weapons. Though Austria is catholic, Wrocław continues to be protestant.

- 1702: The Habsburgian-Austrian Emperor Leopold I founds the university of Wrocław as the Academy of the Jesuits.

- 1741: The last Bohemian king, Ludwig II, dies in the War against the Turks.

1741 – 1945: Under Prussian Rule and from 1871 part of newly founded Germany

- After the wars of Silesia, Frederic II integrates Silesia in the Prussian empire with its centralistic government. The Slavic population is under pressure (even more than under the Habsburgians).

- 1807: Napoleon conquers Silesia, tears down the Wrocław/Breslau town fortification and installs a modern town government creating the basis for its economic development towards industrialization in the 19th century; it becomes an economic and cultural centre as a well as a railway hub.

- 1871: The state university at Wrocław/Breslau is founded.

- After the First World War (1914-18) Wrocław/Breslau becomes an economic and cultural centre again, satellite settlements are built around the city centre.

- 1933: Wrocław/Breslau is part of the fascistic machinery.

- 1945: Having been spared from the war until January 1945, the city is declared the “Fortress Breslau”. The Soviet Army sieges Breslau for almost three months. The city surrenders on May 6th 1945. It is in ruins (67% of all buildings destroyed, Dumont says on p. 245) and the death toll is high).

1945 until today: Again Polish (like about 1000 years ago)

- 1945: Still in May, Poland takes over, based on the Potsdam agreement between US, UK and SU. The remaining Germans are expelled and Poles start to settle, above all from the part of Poland that was integrated into the Soviet Union (Poland was basicaly shifted to the west). The city is now called Wrocław, no longer Breslau.

- End of the 1950’s: Wrocław is an economic, scientific and cultural centre in Poland.

- Late 1970’s: In Wrocław, the Orange Alternative (Pomarańczowa Alternatywa) organizes humorous events to make fun of the communist regime (leader: Waldemar Fydrych )

- 1989: After the fall of the iron curtain, Wrocław is thriving economically and as a centre of tourism. Like other major cities in Poland such as Kraków or Warszawa.

- 2000: Wrocław celebrates its 1000 years anniversary. The circle closes. The city was Polish then (until 1335) and now belongs to Poland again.

Sources: