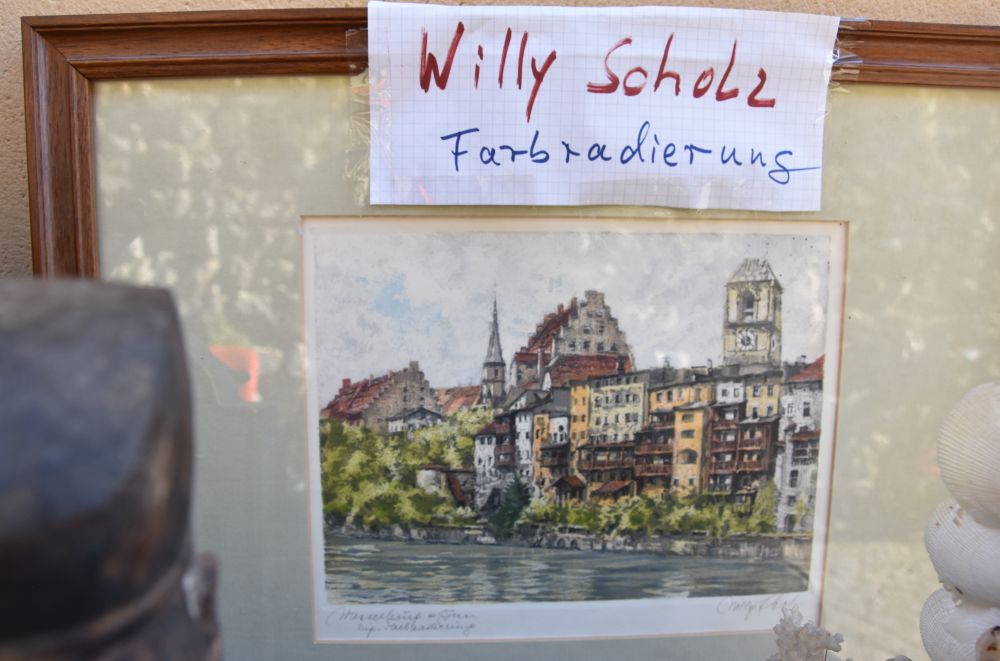

My grandfather Hermann Radzyk painted the angler at the Löcknitz in 1921. I believe, I found the location of the easel in September 2025.

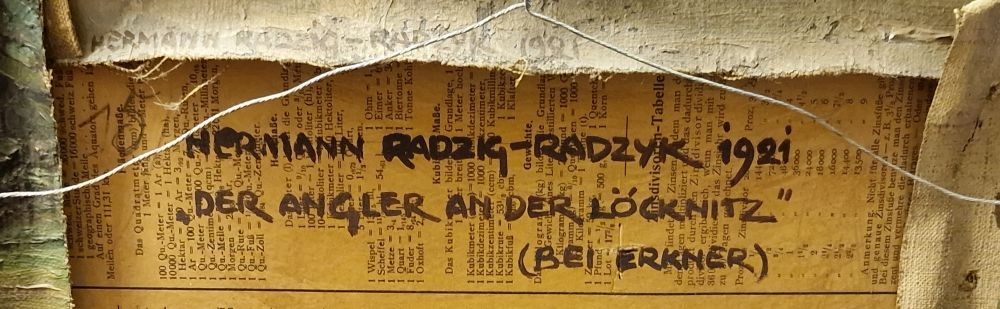

This is “der Angler an der Löcknitz”, signed Hermann Radzig-Radzyk and dated to 1921.

Let us look at the details: The river Löcknitz is meandering. Both shore areas are flat meadows. Two influxes feed the Löcknitz from the left. On the right river bank my grandfather painted another angler and some people walking (perhaps along a path). Behind the meadows, there is a slightly elevated line of bushes or trees. In the bushes above the meadows, I believe, I can identify a small house in the top left corner.

On the back my grandfather added the year, the title and “bei Erkner” which means “close to Erkner”.

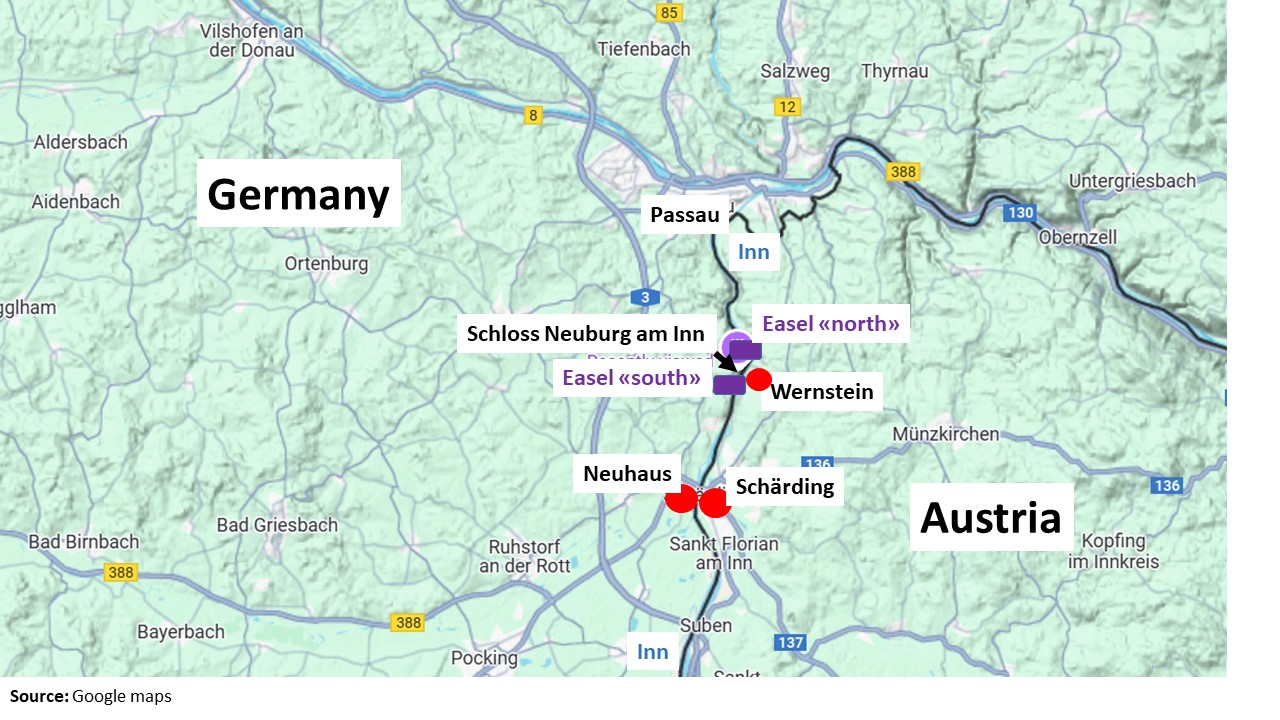

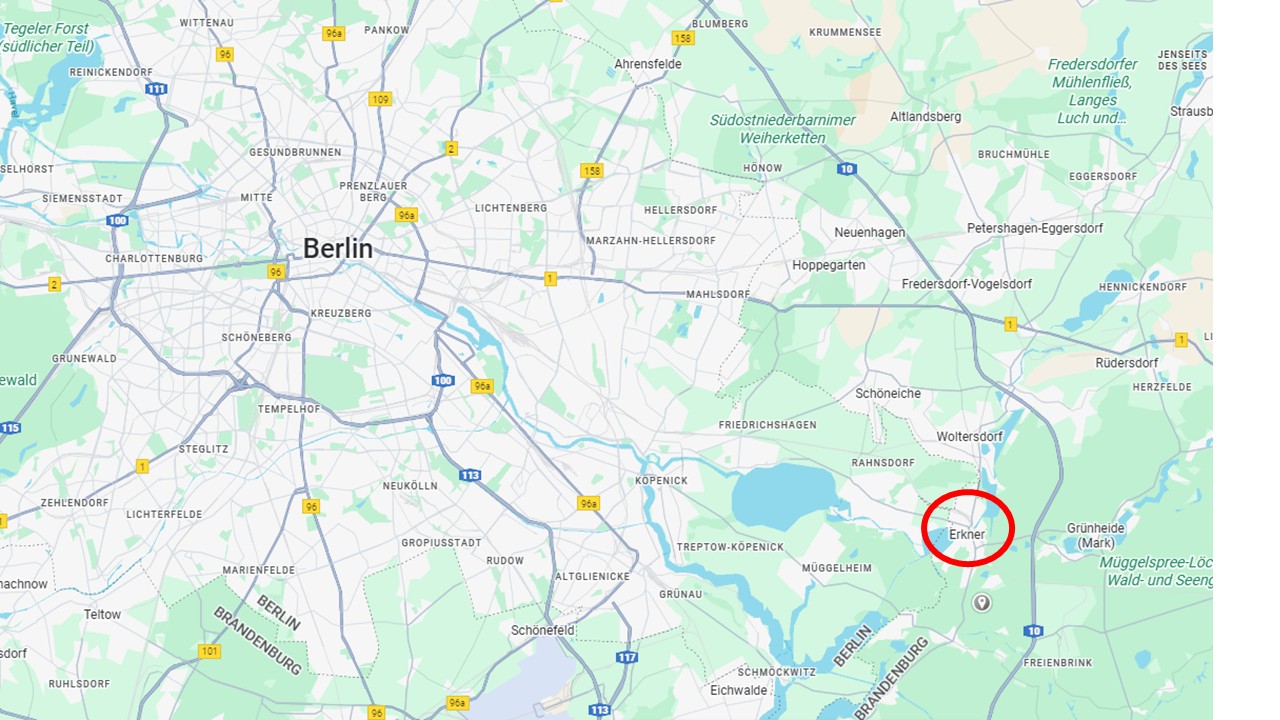

Where is Erkner located?

Let us first see, where we are: Erkner is a small city in Brandenburg, at the border with Berlin.

Source: Google maps, January 2026

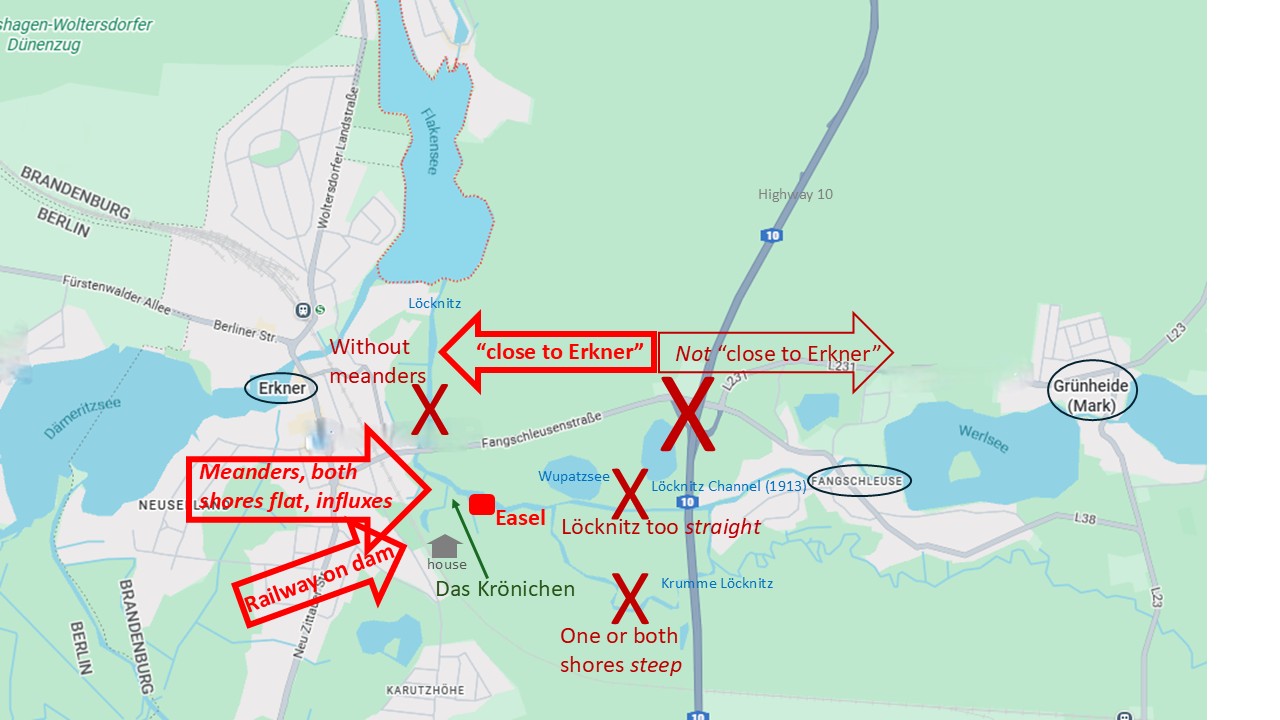

Identifying the landscape by analyzing maps and comparing this with my observations on site

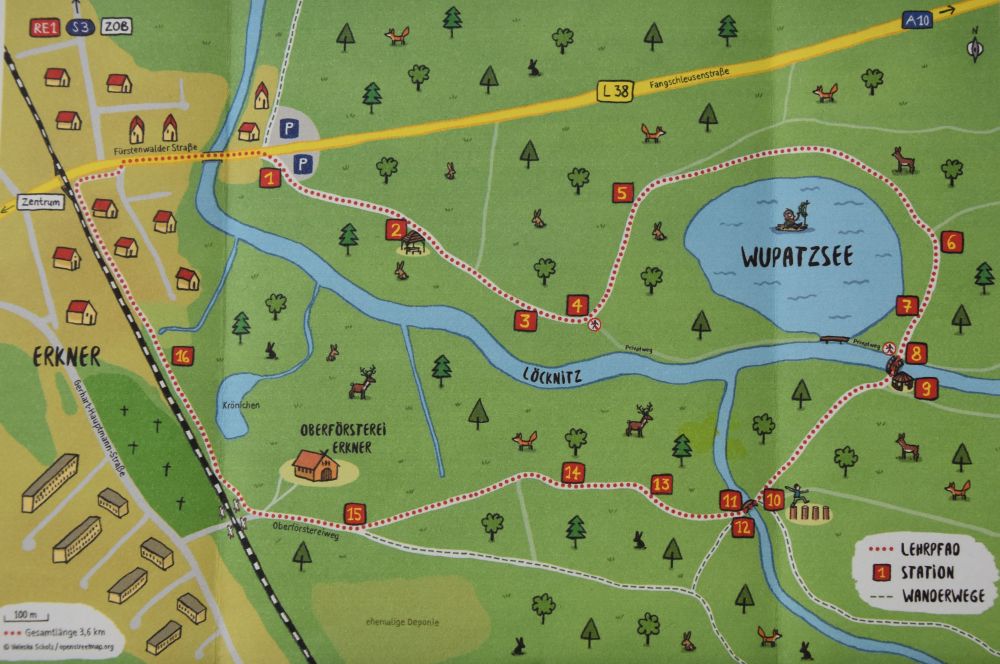

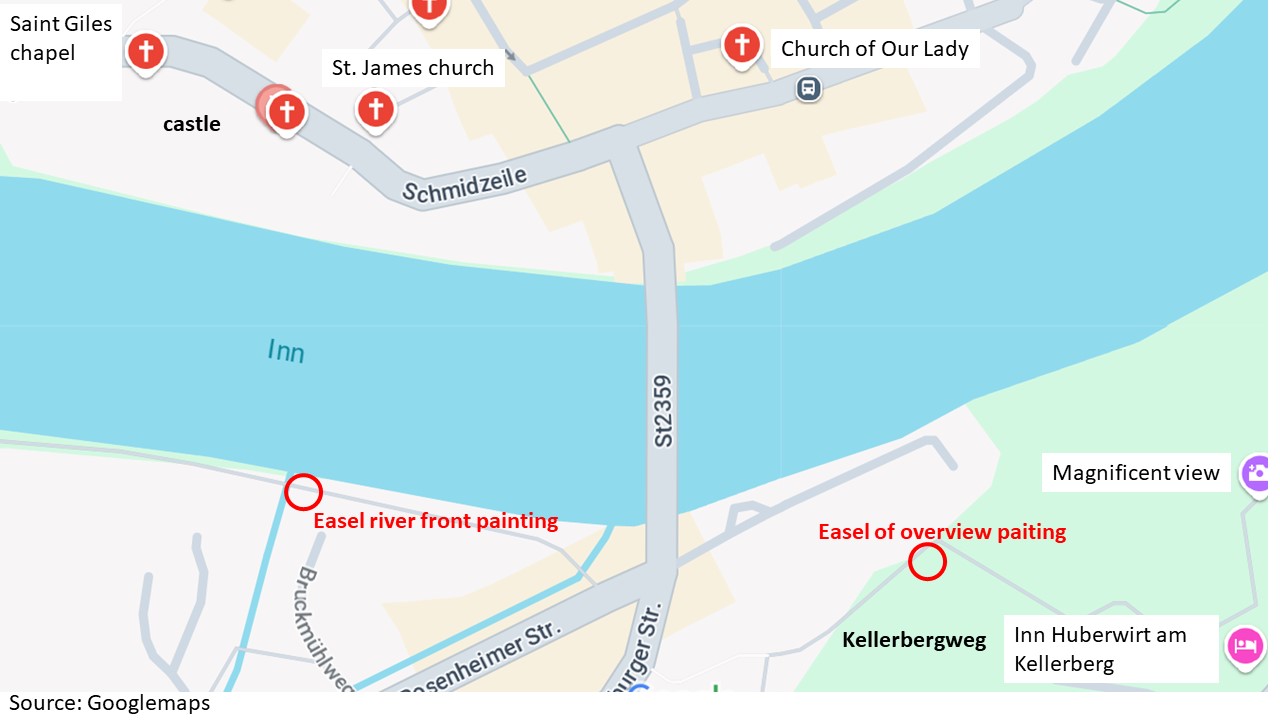

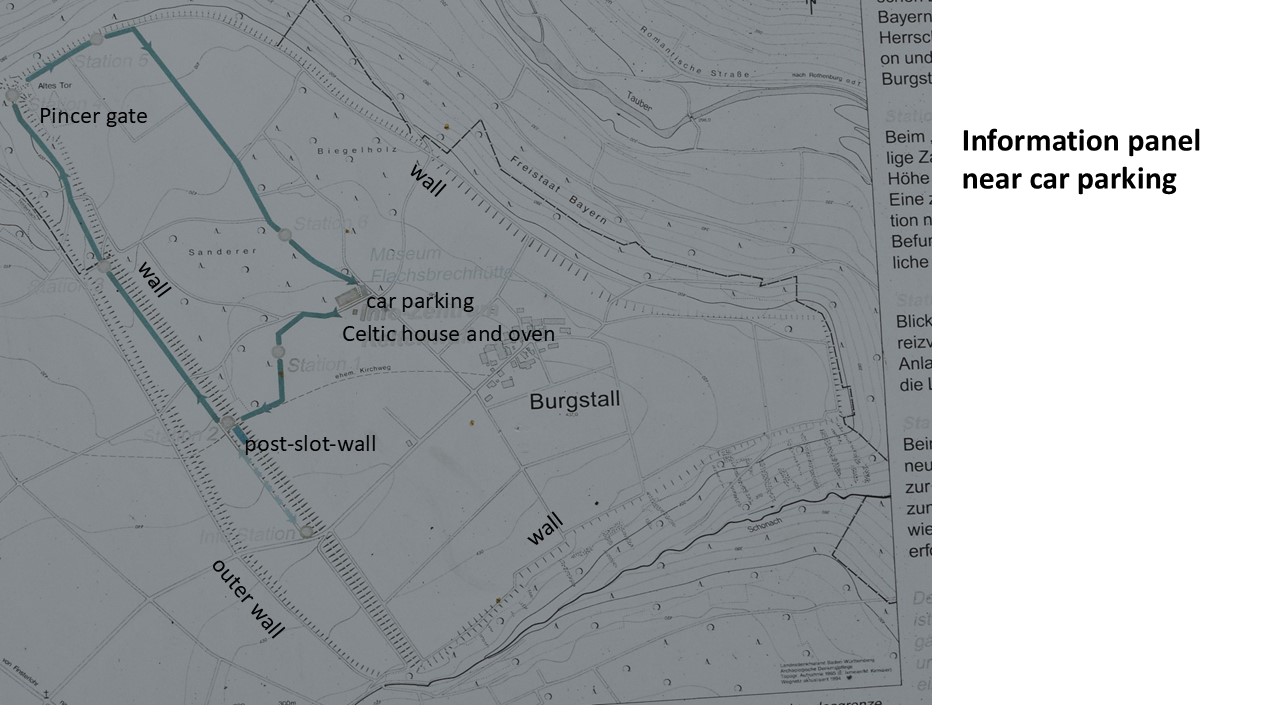

Five times I took the Berlin S-Bahn S3 to Erkner to look for the location of the easel. A hundred years ago, the banks of the river Löcknitz were accessible – this is, how my grandfather could paint his angler at the Löcknitz. But now the banks are largely covered with trees – mostly inaccessible. This makes it difficult to identify the location of the easel. Only by combining my observations with Google Maps and the forrester’s map Arcanum of 1877, I was able to narrow down the location of my grandfather’s easel, and I am pretty sure, I found the approximate location.

Source: Google maps with my annotations (map accessed in January 2026).

Let me explain: On the map, I crossed out the implausible areas (X) to narrow down the probable location of the easel.

(1) My grandfather wrote “bei Erkner” or “close to Erkner”. He was always precise, hence “close to Erkner” means that his easel was closer to Erkner than to the next village Fangschleuse.

(2) In 1912/1913, a channel was built to link Erkner directly to the Werlsee and allow shipping. This channel already existed in 1921, when my grandfather painted the Löcknitz, but it is too straight; no, not here; the easel stood, where the Löcknitz was meandering.

(3) What is called “Krumme Löcknitz” (south of the Löcknitz channel) is meandering, but along the “Krumme Löcknitz”, one or both shores are steep (I climbed around here); no, not here; the easel stood, where both banks of the Löcknitz were flat.

(4) Before flowing north and into the Flakensee, the Löcknitz is mainly without meanders and it was without meanders already in 1877, as the historical Arcanum map below shows; no, not here; the easel stood, where the Löcknitz is meandering.

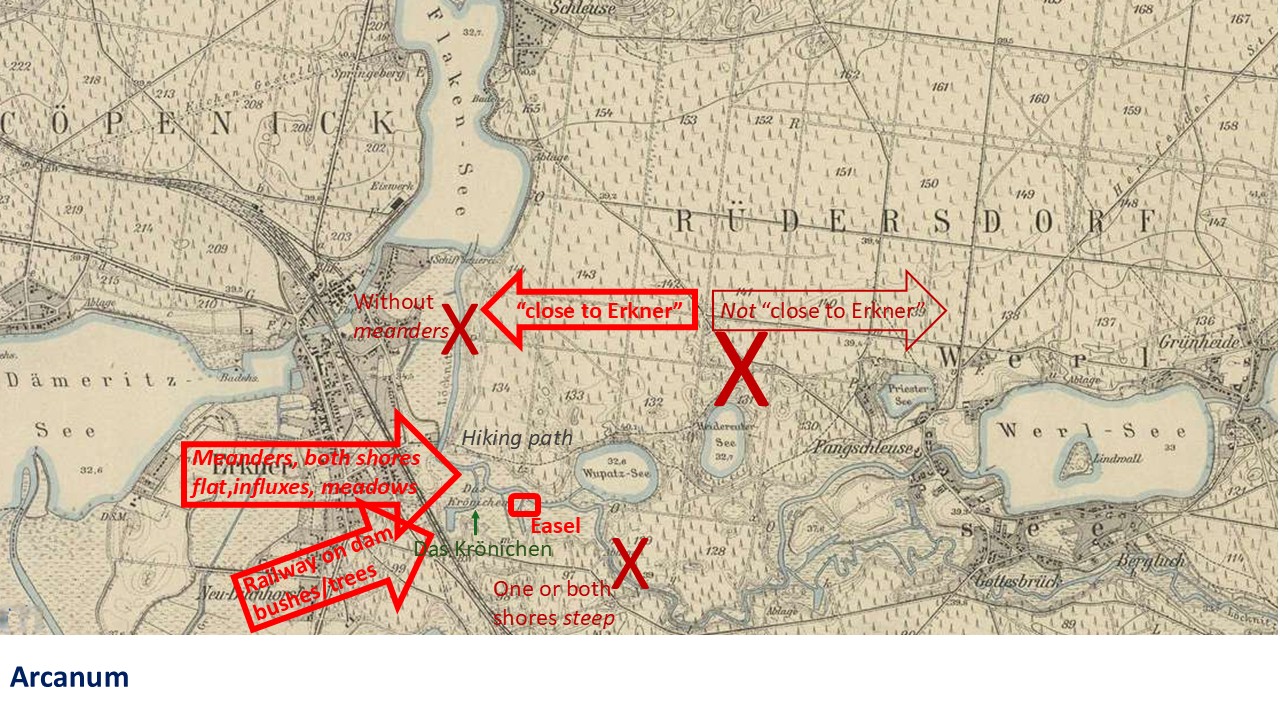

Source: Historische Karten Preussen, Forst Erkner 1877 accessed in Januar 2026 (the railway was constructed in 1877),

https://maps.arcanum.com/de/geoname/germany/forst-erkner-2929601/

(5) The historical Arcanum map of 1877 shows that at the “Das Krönichen” both river banks were flat meadows. In addition, it shows the railway (built in 1842); the rails are on a dam, where the land rises up to about 100m, says the map. This is higher than the meadows at “Das Krönichen” (altitude on Wupatzsee: 32m). On the historical map, the higher area is covered with bushes or trees, already in 1877. This matches: Flat meadows and in the background elevated bushes or trees, that is, what my grandfather painted in 1921.

(6) On the historical Arcanum map, the meadow on the right shore is bordered by a forest with a hiking path along the edge of this forest; the hikers on my grandfather’s picture behind the meadow could well be walking on a path along the edge of the forest.

(7) What about the house in the top left corner of my grandfather’s picture? Today the forest rangers have a house here, but it was built later than 1921, only in 1929. Before 1929, there was perhaps a tumbledown house here used by peat diggers, as I understand from the local historian. Hence it could well be that my grandfather saw (and painted) a small house in the top left corner of his picture.

As the area around “Das Krönichen” is the only place, where the Löcknitz meanders “close to Erkner” and where both river banks are flat with influxes from the left, I am pretty confident that the easel was at “Das Krönichen”. Compared to 1877, the influxes from the south have slightly changed today (the local historian told me that for “Das Krönichen”, small river bank fortifications are known). My grandfather must have stood behind one of the influxes, presumably behind the first one after the Wupatzsee, which gave him the full overview of the (at that time still existing) meadows and the elevations in the background.

These are my guesses. I was not able to access the place, where I assume the easel was. “Das Krönichen” on the left bank (downstream) is covered with trees; I could not find a path to get to the influxes. Neither could I find a path to get behind the forester’s house to the edge of the elevation above the meadow or to the pond below it.

To verify my guess, I took the commercial boat from Erkner to Grünheide.

At “Das Krönichen”, my first photo from the boat shows the left bank (left downstream), where I assume the easel stood on the (flat) meadow. Today there is dense forest here, on flat ground. This is as much as I can see from “Das Krönichen”, when passing by by boat.

My second photo from the boat shows the meadow on the right river bank (right downstream). From the river, trees hide the view of the meadow, except for this “window”.

When walking back from Grünheide, I accessed this “window”, with the view of “Das Krönichen” across, where the easel must have been. Just trees all over.

Later, I looked at the meadow from the hiking path that already existed in 1877 and still exists today. I cannot see the river Löcknitz, trees hide the view.

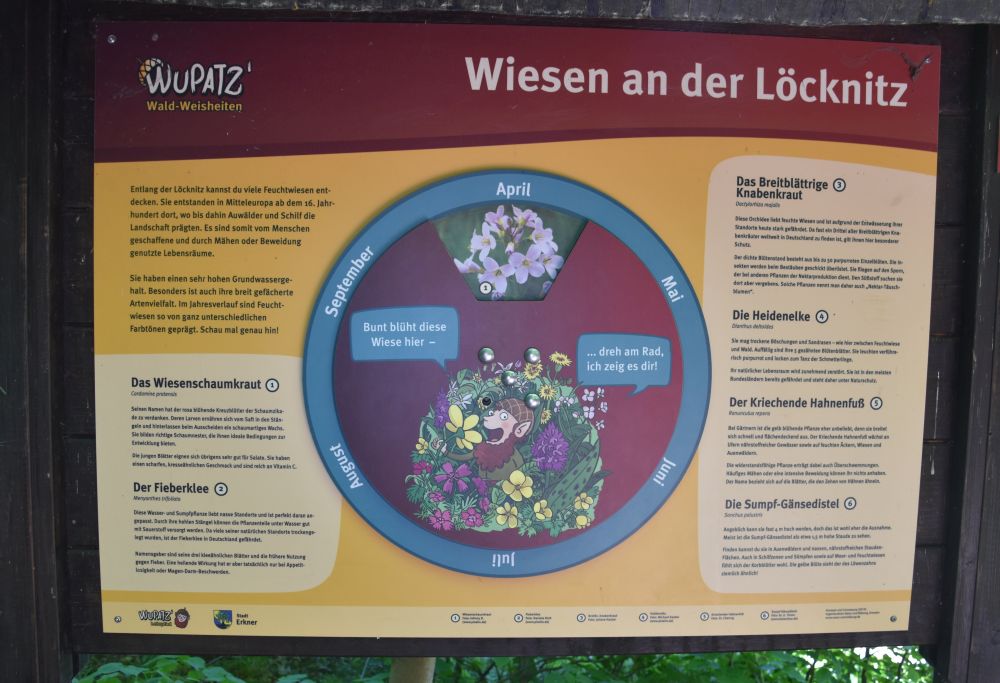

The explanatory panel of the Wupatz Path says that this is a damp meadow bordering the river Löcknitz.

Well, my grandfather could no longer paint his picture today. The area around “Das Krönichen” has become an inaccessible nature reserve. Good for nature.

It was a great pleasure to explore the area around Erkner; it is worth a detour with its lakes and rivers

The above explanatory panel is part of the Wupatz Path that teaches children knowledge about the forest (Waldweisheiten).

The path is called after the romantic Wupatz lake (Wupatzsee).

The Löcknitz channel is separated from the Wupatzsee by a small land bridge (photo taken from the boat).

On and near this bridge, I met anglers and a photographer. One angler, a German not far from Erkner, was frustrated: He caught not one fish, and the group of lucky men nearby caught one fish after the other, were not pleased with the size and threw them all back into the water. The successful anglers invited me to sit down and share sandwiches with them. Behind the bridge, a photographer was enthusiastic about dragon-flies. He explained the differences to me – some are rare, some are more common… and he took one photo after the next with his professional looking camera.

The Hubertussteig (wooden bridge) crosses the Krumme Löcknitz. Panels tell the children about the fish that live in the area: rudd, river perch and pike, and these are just a few out of almost twenty species.

The Löckntz was and is an anglers’ paradise. No wonder that my grandfather painted an angler at the Löcknitz.

Where the Löcknitz flows north towards the Flakensee, Ernker has established the Theodor Fontane Path, and it starts with this poem:

“On a summer morning, take your walking stick, all your concerns will fall off from you like mist”. Panels with poems by various poets line the Fontane path; the poems match the trees.

Shortly before the Löcknitz enters the Flakensee, I found this this small resting place, where I met more anglers.

Later the Löcknitz flows in the Flakensee; this lake attracts the Berliners with camping and picknick sites.

At Woltersdorf, I took the tram; it climbs up a hill (a hill here, what a surprise…) and brings me to the S-Bahn station Rahnsdorf, where I took the S3 back to Berlin.

I have just included a few sample photos that I took, when walking near Erkner. Yes, the lakes and rivers here are worth the detour.

Thank you, my grandparents, you showed me another wonderful place

So many times already my grandfather’s pictures took me to wonderful places, this time with the picture “der Angler an der Löcknitz”. Thank you, my grandparents, I enjoyed exploring the rivers and lakes around Erkner, and I will return to show the area to my friends that grew up in Berlin, but could not get to Erkner at that time because of the inner-German border. I am sure, they will also like the area.

Post Scriptum: Some history of Erkner

Erkner started as a small fishermen’s hamlet. In 1712, it became a stop on the postal line from Berlin to Freiburg an der Oder. In 1752, the Prussian king Frederick the Great had 1500 mulberries planted. The plantation was unsuccessful and was soon given up. Today one single mulberry tree is left on the main street.

This tree survived the bombings of the Second World War, and Erkner is proud of it: A mulberry tree with fruit decorates the coat of arms of Erkner.

In 1860 Erkner was declared a climatic spa village; tar was produced here, and the exhaust fumes were considered to be healthy. This attracted Gerhart Hauptmann who lived at Erkner from 1885-1889. Bechstein, the producer of the famous Bechstein pianos, built his summer villa in 1889; the villa is now the Erkner townhall.

Bechstein is well remembered at Erkner; the Italian Ristorante di Piano carries his name.

Since 1842, Erkner has been a train stop on the railway line from Berlin to Freiburg an der Oder and to Breslau, and since 1928, it has been an S-Bahn terminal stop, now S3. The train connection made Erkner and its beautiful surroundings popular with the Berliners.

Sources:

- Mail by Frank Retzlaff, Erkner, 30.08.2025 (Around 1910, a channel was planned, but the inhabitants of Erkner and Berlin protested, because the Löcknitz landscape was a popular recreation area; as a compromise, the channel was built in 1912/13. For the Das Krönichen, only river bank fortifications are know, no precise records exist).

- Mail by Guido Weichert, 04.06.2025 (mentioned that formerly there were meadows on Das Krönichen)

- Mail by Köpenicker Fischerverein, A. Krüger (he gave me the name “Krumme Löcknitz” that is not marked on the maps. He assumed, the picture was painted here, but I could not find two flat river banks along the Krumme Löcknitz close to Erkner).

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erkner

- https://www.familienbuendnis-erkner.de/familienbuendnis/Archiv-Projekt/Erkner-Geschichten/Bechstein-Villa.php

- Panel on the townhall (says that the villa was built in 1889)