In August 2024, I follow the call of my grandfather, the artist Hermann Radzyk, and explore to the Taubertal. This morning, I have just visited the Celtic oppidum, and now, after a few more kilometers, I stand in front of the Herrgottskirche (Lord’s Church) at Creglingen. Here, I am looking for the third altar of Tilmann Riemenschneider that can be found in the Taubertal.

It is a miracle that makes this church special. A farmer had found the untouched piece of sacramental bread in the year 1334. Exactly where the bread was found, the local earl decided to build the church. It was inaugurated in 1396, with an altar at the exact location, where the bread had been found. A window allowed to see the bread and the earth. The church and the altar became a pilgrimage site. This is, what I read in the brochure of the church (p. 1). In 1530, the margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach adopted the protestant doctrine of Martin Luther and introduced it to his territory. As a consequence, the pilgrimage came to a standstill.

I walk around the church. The graceful tower outside is called “Tetzel tower”. However, it is unlikely that Tetzel stood on this pulpit to promote buying indulgence (forgiveness for sins), a commerce that Martin Luther was fighting against. Instead, the pulpit was probably used by the local priest on special occasions.

Before the reformation in 1530, the church made good money due to the pilgrimage. At the end of the 15th century, they decided to acquire several altars for the church. Today, four spectacular altars from around 1500 decorate the church.

The altar of Tilman Riemenschneider attracts the most attention. More dignity was required for the place, where the sacramental bread had been found. The stone altar with the window disclosing the bread was no longer good enough. Between 1505 and 1520, Riemenschneider and his workshop fabricated the magnificent altar of Virgin Mary (Marienaltar). It is 9m20 high and 3.68m wide. The figures are made from lime wood (brochure, p. 21).

I am impressed. The altar of Mary stands in the middle of the nave, in front of the window behind it. I read that this window illuminates Mary from behind exactly on August 15th according to the Julian calendar, then the day of Mary’s Assumption. Today, the light of the window falls on Mary on August 25th, the Gregorian calendar reform of 1582 has shifted the date.

Riemenschneider based his work on some etchings of Martin Schongauer and another master. Mary’s Assumption scene is in the middle, Angels carry Mary to heaven, the apostles are grouped around her, and the gap between the apostles makes it clear that Mary has left the ground. Around Mary’s Assumption, there are four scenes from the life of Mary: Annunciation by archangel Gabriel, Visitation (Mary – pregnant – meets Elisabeth, then also pregnant with John the Baptist), the birth of Christ in the stable and the Circumcision of Christ.

Above, there are the Coronation of Mary and Christ as the Man of Sorrows.

In the predella, we see the three Magi to the left…

… and Jesus teaching at the school of Zachaeus to the right.

In the middle, there are two angels – it is assumed that the monstrance with the sacramental bread stood between them, but it is lost. Luckily we have not lost more of this altar.

Soon after Riemenschneider’s altar had been installed in the church, the reformation took place. The reformers wanted to destroy the altars in the church. The priests and the citizens of Creglingen closed Mary’s altar and hid it away behind a board wall. The place became a shed for wreaths, and soon the altar was forgotten. About 300 hundred years later, probably after 1800, the altar was opened up again. Only, because there is a portrait of Riemenschneider in the predella, we know that the altar has been created by him. Fortunately, he has left his signature. And because on the “old” Assumption day, the light falls precisely on to Mary from the rose window behind her, it is clear that Riemenschneider has designed it for this church. What a story!

I spend a long time in front of Riemenschneider’s altar studying the vivid expressions in the faces, the fall of the folds and the shadowing. Riemenschneider WAS a master.

There are more wonderful altars in this church, all made around 1500 to support the pilgrimage still active then.

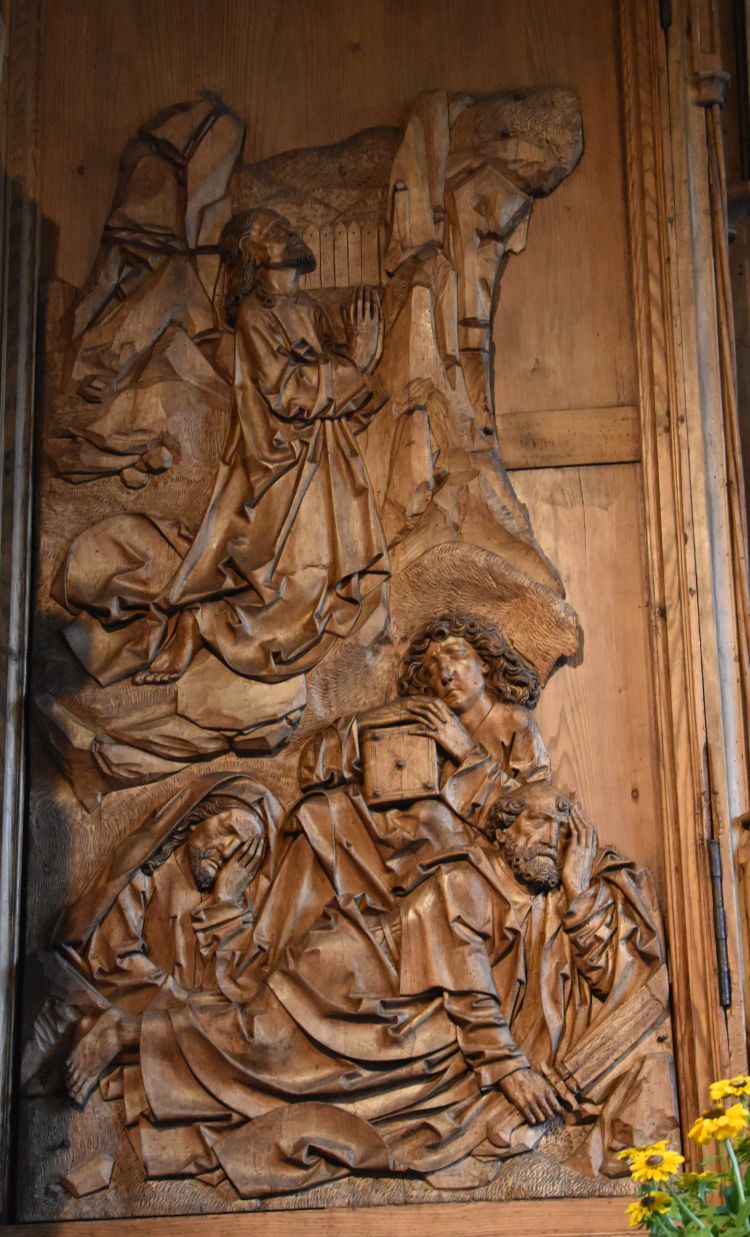

The main altar stands in the choir. The artists are not known. The altar shows the Passion of Jesus with the crucifixion in the middle, two events before it (Gethsemane and Carrying of the Cross) to the left and two events after it (Entombment and Resurrection) to the right.

The northern side altar illustrates the engagement of Mary and Joseph (the Virgin Mary is already pregnant), the birth of Jesus and the scene with the Three Magi in the middle. In the predella are two beautiful paintings, to the left the evangelist Markus, to the right Matthew. Matthew prays intensely looking to heaven, an angel watches him. The liveliness reminds of Renaissance paintings.

The southern altar shows various Saints and martyrs. In the predella, I recognize Moses on the side wing next to the Last Supper, .

I do not understand, why Moses has horns, it may be something like a gloriole, but this is, how I always can identify him. The scene shows the wonder of the bread in the desert.

Before leaving the church, I greet Christopher – the fresco is from the beginning of 16th century.

He is the patron saint of the travellers and the means of transport, and I am a traveller right now.

I leave the church. On the one side of the entrance are the wrangler (in German: Streithähne which translates literally to “quarrelling cocks”; the two cocks are the illustration of the wranglers).

On the other side is the “sceptic” – the man robbing his beard seems to be in doubt, he is sceptical.

The wranglers and the sceptics have to remain outside the church. What a nice symbol.

I leave the wonderful Taubertal now and drive north towards Berlin.

Sources:

- Sabine Kutterolf-Ammon, “Die Herrgottskirche zu Creglingen”, Kunstschätzeverlag, Gerchsheim 2016. (Brochure)