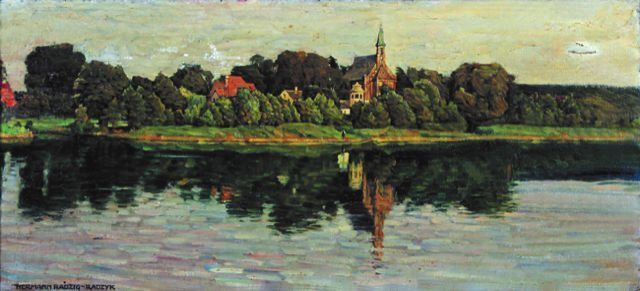

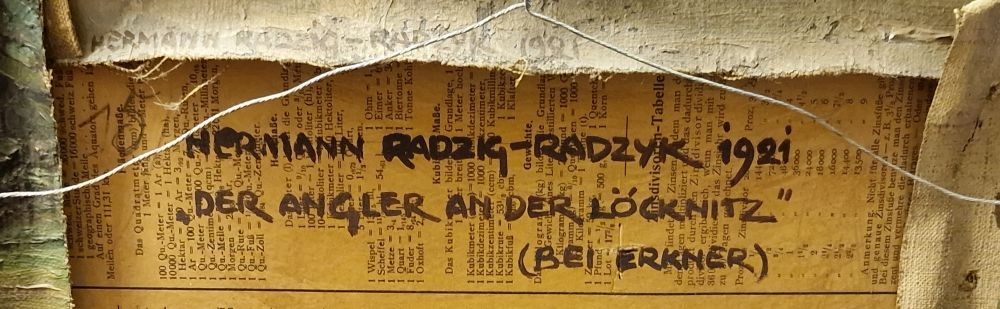

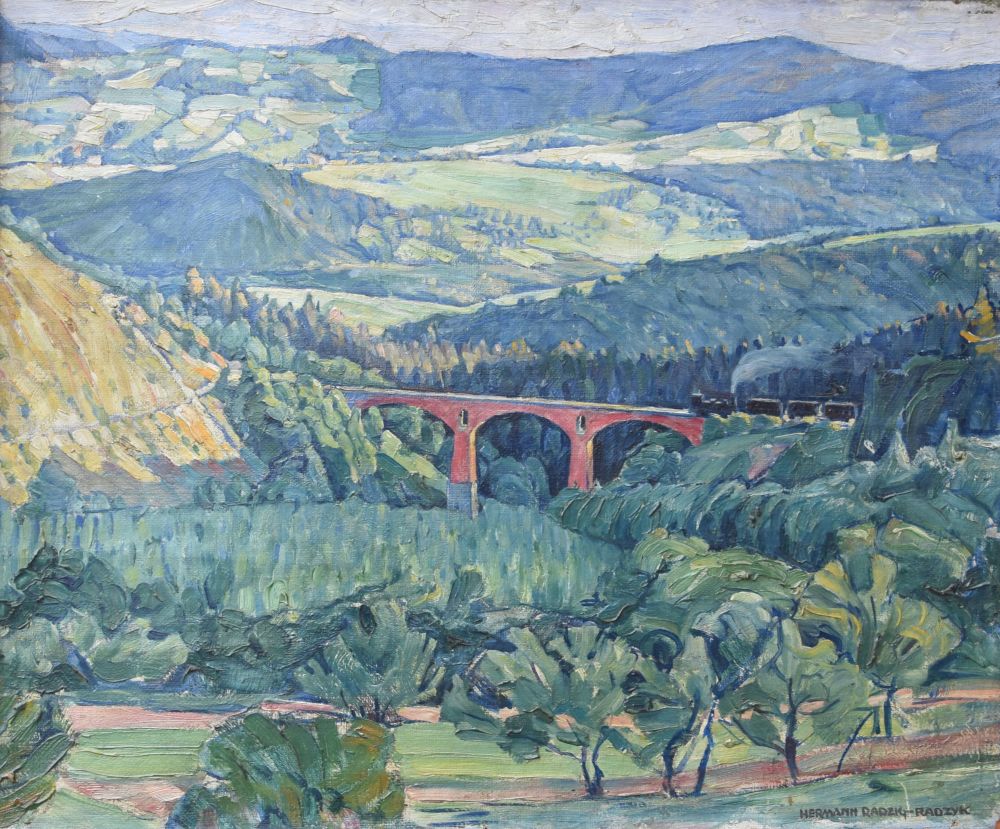

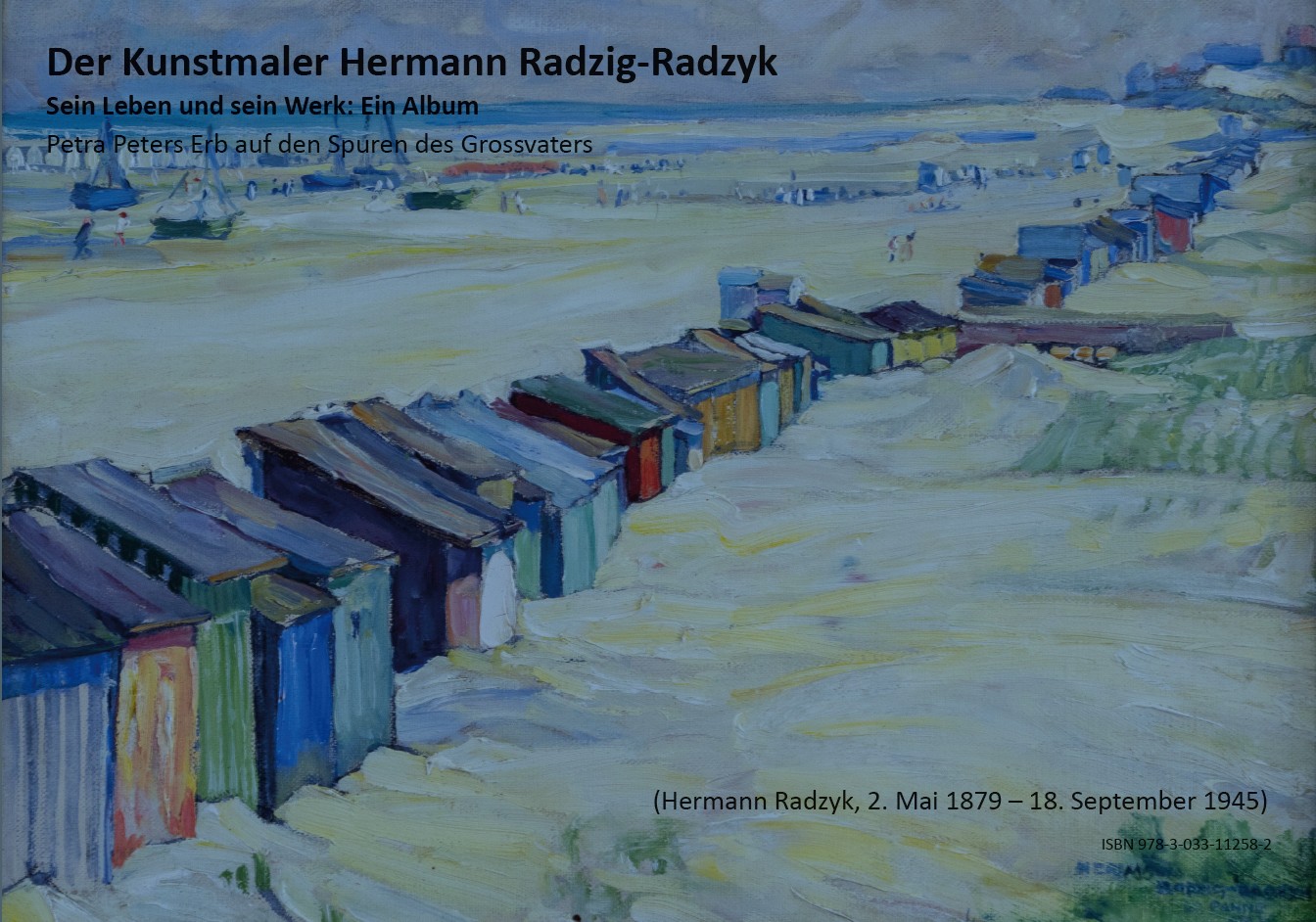

In 1932, my grandfather Hermann Radzyk created two paintings at Geising in the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains), south of Dresden.

The first painting hangs in my home. At the back, it carries the title “Geising im Erzgebirge”, is signed with Hermann Radzig-Radzyk and dated to 1932.

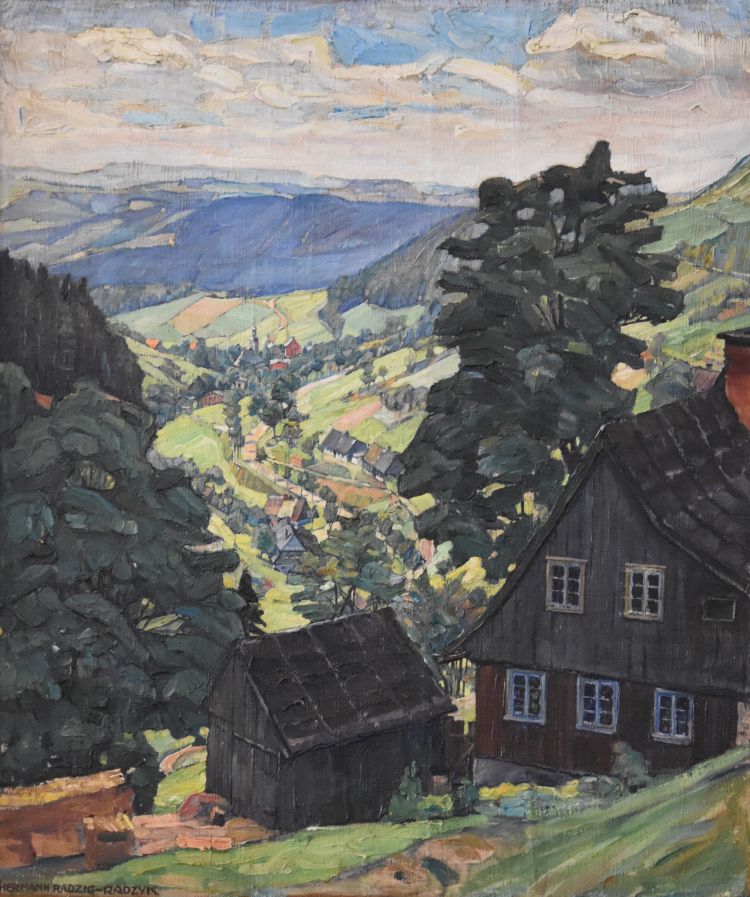

The second painting belongs to my sister. It has no title, is unsigned and undated. It shows the same church of Geising and must have been created in 1932 as well.

The second painting has a daunting history. Let me tell you.

The painting decorated the living room of my grandparents in their house at Kleinmachnow, Haberfeld 5.

The photo of 1940 is from the wedding album that my mother assembled, when she, still called Marion Radzyk, met my father, Rudolf Peters. With her mother Helene Radzyk, she arranges flowers, the painting hangs behind them. Furthermore her bust (she was then about 17 years old) stands in the corner.

I came across the painting in the home of my sister. It had a sad look: No frame, dirty and damaged, some holes.

In the Second World War, the house of my grandparents was damaged and surely this has caused the holes. After the War, Kleinmachnow was part of the Soviet Zone. When my grandmother died in 1953, my mother went to Kleinmachnow for the funeral. She described in her diary that she packed some of her father’s paintings and her bust in a bag and crossed the zone border to West Berlin without being stopped by the customs officers – luckily. I am pretty sure, this is how the painting of the Geising train station ended up in my mother’s house and later in our hands.

I had the severely damaged painting cleaned and repaired by my gallery in Basel.

It shines again in fresh colours. Only now I take notice of the two ladies next to the bridge, my grandmother Helene with her daughter Marion – my mother.

How did I find out that not only the first painting (with the title), but also the second painting (without the title) is from Geising?

The first painting carries the title “Geising im Erzgebirge”. This was easy. The old postcard illustrates my grandfather’s perspective with the mountain Geisingberg north west of the small city.

Source: Mail by the historian of Geising from May 8th 2024

The second painting carries no title. I guessed that the church is also at Geising. Googling, I found the postcard that clearly confirmed my guess.

Source: Ansichtskartenlexikon, Stadtpartie, Bahnhof: Geising-Altendorf (Erzgebirge).

Consequently, I planned a stop at Geising, and end of April/beginning of May 2024, I booked a room in the hotel Ratskeller at Geising to look for the paintings.

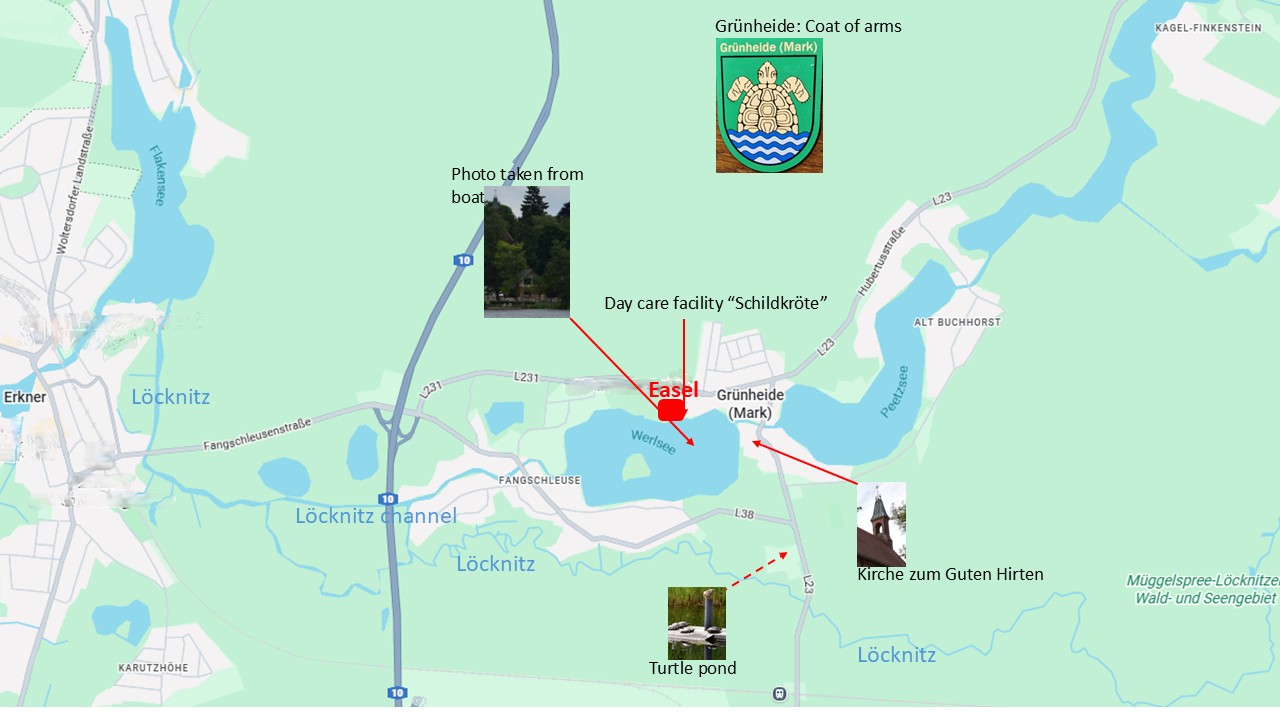

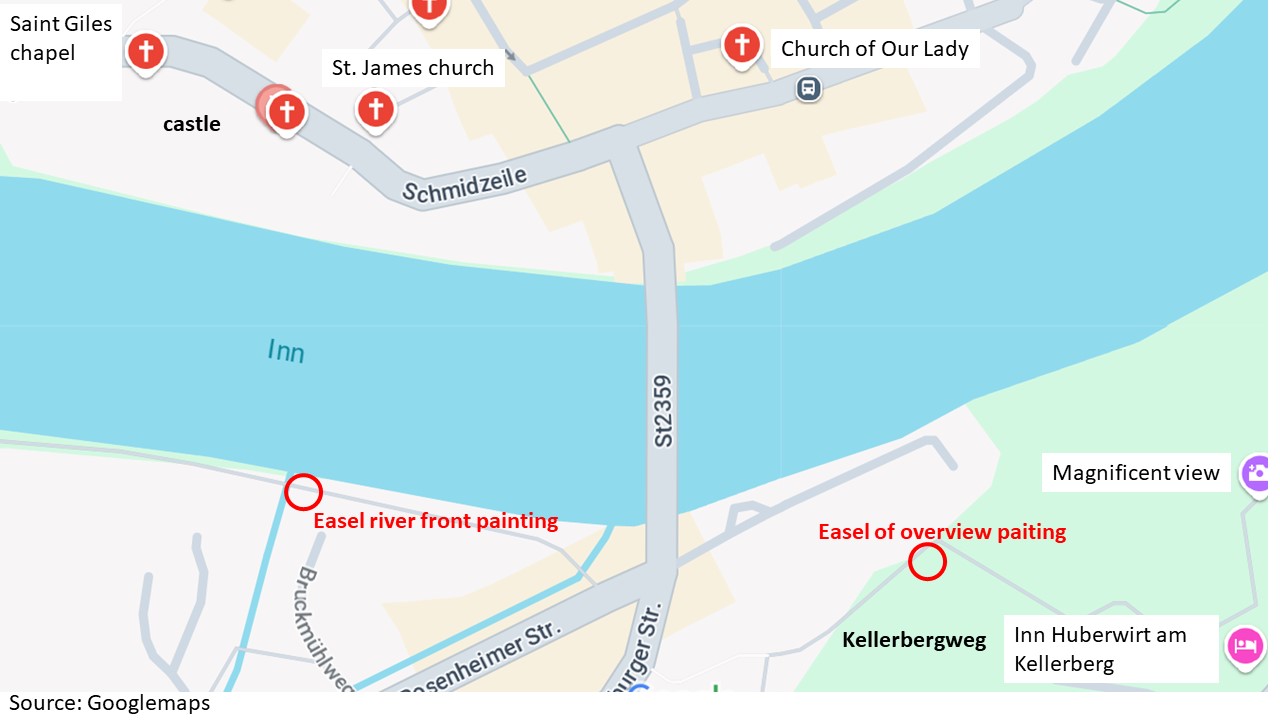

Where did Hermann Radzyk put down his easel at Geising?

Let us tackle the first painting – church and mountain Geisingberg.

His easel was higher and more to the left than my photo below; between him and the village was a field with a footpath and a few small trees. Now the field is covered with newly built houses, and there are gardens with big trees.

I walked uphill between the houses, and up to this point, I could see both the church and the mountain Geisingberg in the background. Going farther uphill to get to the location of the easel, the church and the mountain disappeared behind the houses, the gardens and the large trees. Today, Hermann Radzyk could no longer paint his perspective today.

Also the second painting with the train station is no longer possible today.

The train station looks different, the church in the background can barely be seen. The bridge is much larger. A busy road coming from Altenberg crosses the railway here. I am standing a little too low; my grandfather stood to the right of the bridge on the footpath leading to the mountain Geisingberg.

On the hiking map, I marked the locations of the easel.

Source: Osterzgebirge zwischen Dippoldiswalde und Teplice (Teplitz), Wander- und Radwanderkarte mit Reitwegen, 1:33’000, Herausgeber: Sachsen Kartographie 2022.

The easel for the first painting (red circle) stood above Geising looking north-west towards the church and the mountain Geisingberg. The easel for the second painting (purple circle) was at the entry of the road from Altenberg to Geising above the bridge, looking south east towards the mountain called Hutberg.

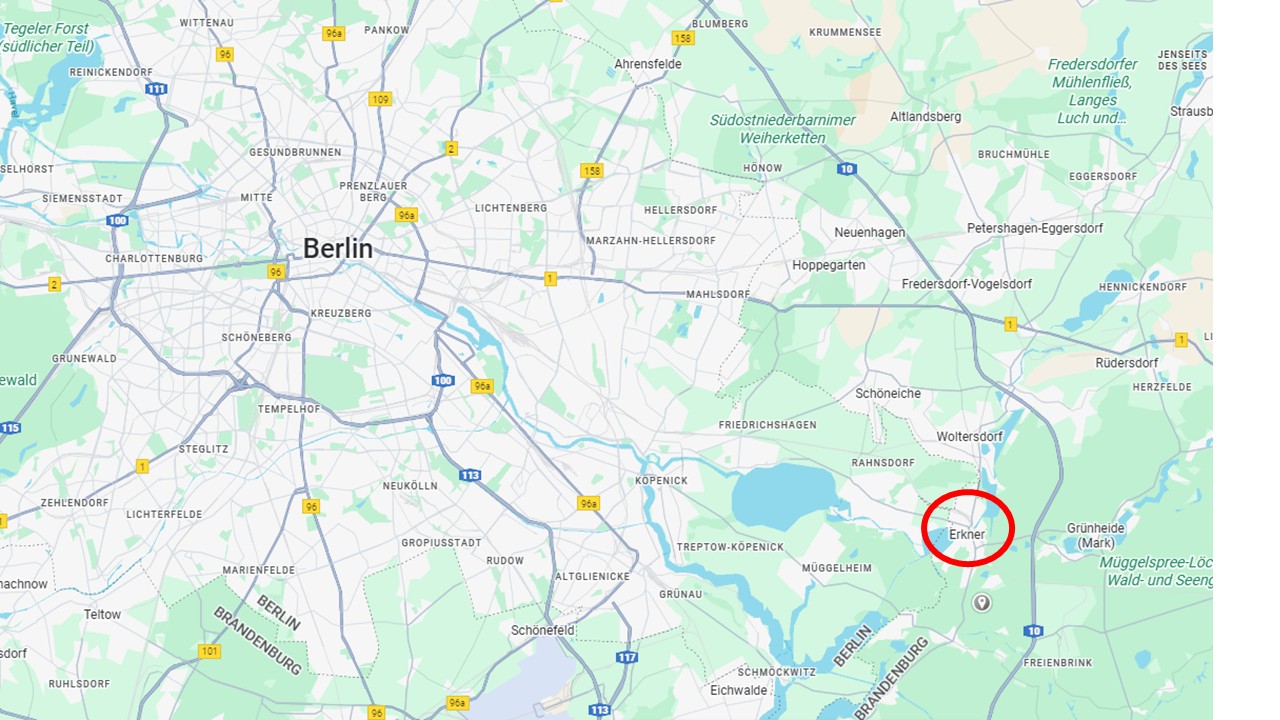

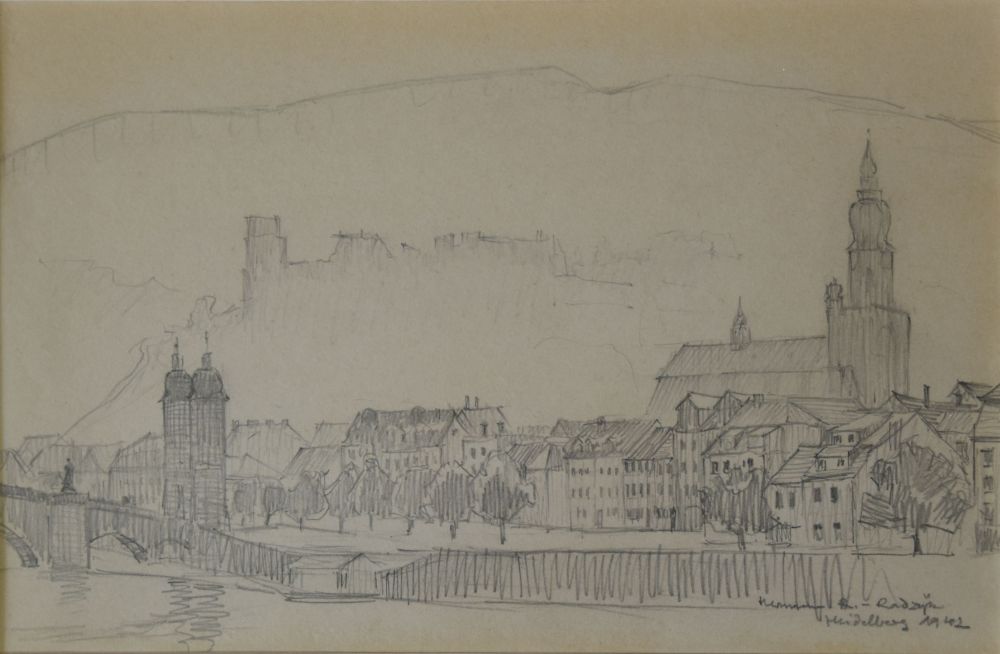

Geising is located 45km south east of Dresden, in the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains) and at the border to Czekia. I have marked Geising with a red circle.

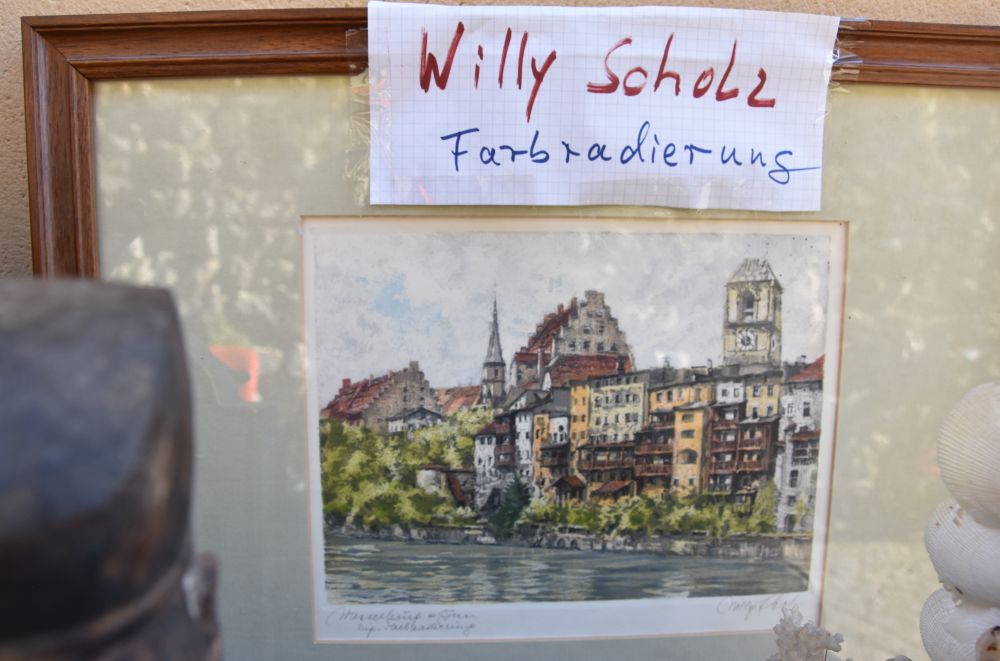

Why Geising, were there more artists at Geising?

While strolling through Geising, I met many friendly citizens. They noticed my camera and asked me: “What are you doing?” When I showed them the paintings of my grandfather, they gave me hints and told me about other painters at Geising.

Very proud they are of Heribert Fischer-Geising (1896-1984) From 1919 to 1961, he lived at Geising, and he integrated the city in his name. Not far from Geising, the castle Lauenstein hosts an exhibition of his paintings. Fischer-Geising painted landscapes and portraits. He was not only an artist, but also a ski teacher that won medals. For one of his paintings he chose about the same view as Hermann Radzyk – church and mountain Geisingberg in the background. It could well be that my grandfather met Heribert Fischer-Geising.

Ewald Schönberg (1882-1949) was born at Geising and lived at Dresden. His style is “New Objectivity”. In particular, I like the red horse that had escaped the master. He is about the same age as my grandfather and, like my grandfather, by his first education he was a carpenter. Perhaps they met at Geising.

In addition, the citizens mentioned Curt Querner (1904-1976). He was born in a village near Geising. Also his style counts as “New Objectivity”. One of his self portraits is in the National Gallery at Berlin. He is younger than my grandfather.

Exploring Geising, another place that my grandparents attracted my attention to

I felt welcome at Geising. The hotel Ratskeller is modest and cosy.

The owner is friendly. He welcomed me with a smiling breakfast egg, how kind.

For dinner, the owner serves beef olive with red cabbage and three huge dumplings. With it, I have a dry cuvée from the Elb valley. I eat on the terrace. The meal is well cooked, but I leave the third dumpling, it was too much. The owner understands me and adds: “I always serve three dumplings on the terrace, I do not want passers-by to think that I am stingy”.

Near the station, I found the map of Geising with the main business addresses.

Sport Lohse was very useful. I had forgotten my thermos flask, and Sport Lohse had flasks. The lady behind the counter recommended the Sigg flask to me. Oh, yes, I know Sigg. It is a Siwss company. I bought a new black Sigg thermos flask in the middle of the Ore Mountains. I tell you, this flask is of high quality. Still after a day, my tea is warm.

The Nestler Café is another recommendation on this panel. Nestler has his pastry shop just next to the train station.

Father Nestler asked me: “What are you doing here?” I walked around the train station behind his pastry shop, where there were sheds, not really a place for tourists. He was assembling a blue plastic flower corner ordered over the Internet; the assembling did not seem to be as straightforward as expected. He listened to me with great interest. “Oh”, he said, “we have old photos of the station, come and see us tomorrow, we are closed today.”

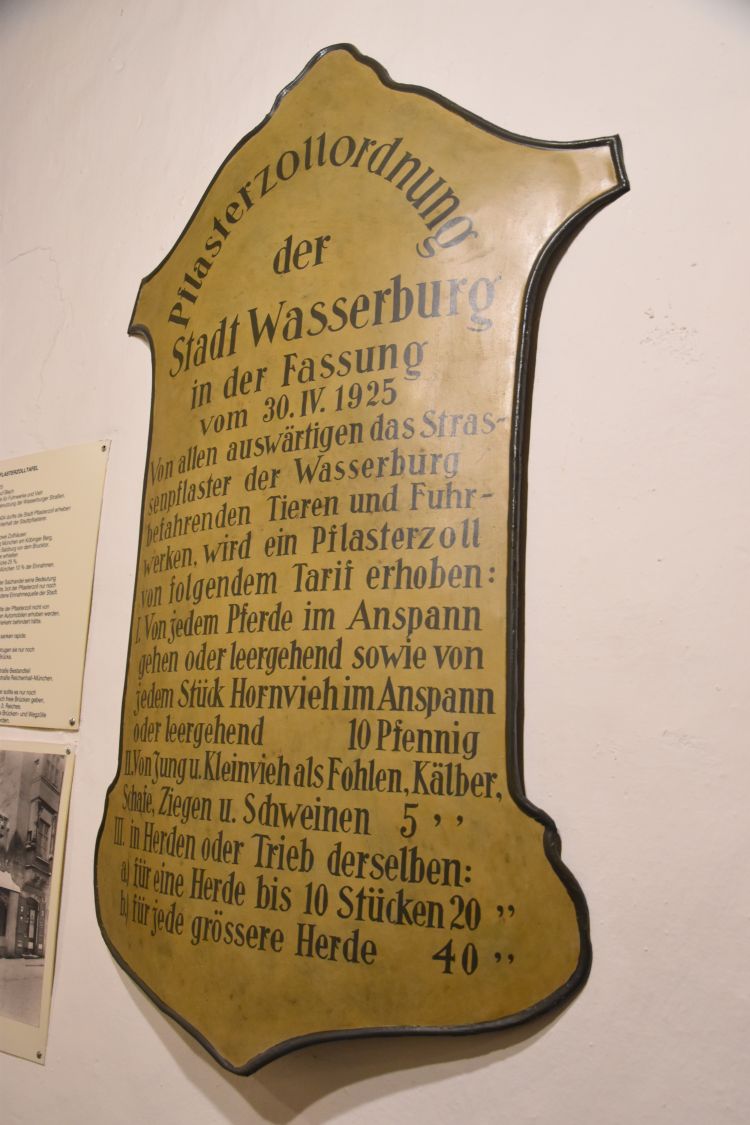

The next day, I met the junior owner of the Nestler pastry. He explained the history of the railway and the train station to me: The narrow-gauge railway was built through the Mützigtal in 1890, from Dresden to Geising. Here, the train ended in a terminus. Only in 1923, the engineers were able to extend the railway to Altenberg above Geising. The ascent was steep and could only be overcome with lighter wagons. A friend of mine told later me that for the ascent of up to 36 promille, special locomotives of type 84 were used.

In 1938, the railway was upgraded to broad gauge, and the station hall was built, as this postcard shows. The Nestler shop later settled in the small house to the left of the train station.

Source: akpool.de

The railway coming from Dresden leads along the mountain Geisingberg. A ditch had been carved along the mountain to allow the train to arrive at Geising without steep ascent.

This is, how the rails hidden in the ditch enter Geising under the bridge (the older version of the bridge is on the painting of my grandfather).

The construction of the railway in 1890 promoted the emergence of tourism. I am sure that my grandparents took the narrow-gauge train from Dresden to Geising.

Let us now explore the small city and the mountain Geising.

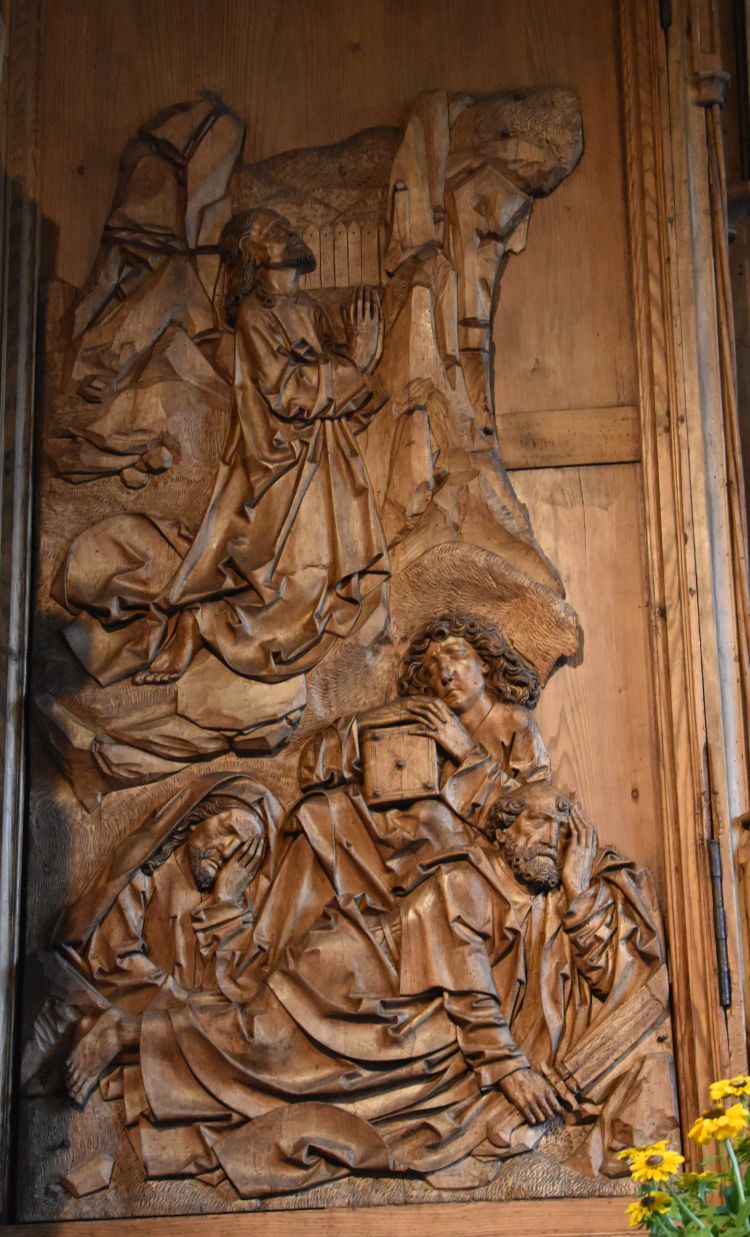

The town church of Geising

The centre of the small city of Geising is the Lutheran town church (Stadtkirche).

A panel explains the history of the Stadtkirche: In 1513 it was consecrated by the abbot of near Altzella. In 1539, the Reformation was introduced to Geising. In the years 1689/90, the church was enlarged.

The main altar is baroque. One angel hangs above the pulpit and the second angel is above the baptismal font.

The well preserved medieval city center of Geising

Ore mining was mentioned here already in 1371. Iron, silver, tin was explored. Two cities emerged, Altgeising to the left of the creek Heerwasser and Neugeising to the right of the creek Both parts of Geising received the town charter in the 15th century and joined later to become Geising. The city layout has remained unchanged since the 16th century. The center is well preserved and is under monumental protection.

I stroll along the streets. Old half-timbered houses make the small city worth a visit. I smile, when I notice the old Trabbie car of GDR times. It stands in front of the Saitenmacherhaus (the name alludes to the producer of strings for music instruments).

Each historical building carries its panel “Häusergeschichten” (house stories alluding to house History). Klaus Meissner has created (and signed) them based on the recordings of the chronicler Werner Stöckel.

The “house stories” tell us that the Saitenmacher House was built in 1490, probably by Hieronimus Knorr. 1686/88, the next owner Wendisch enlarged it. Later it was the workshop of tinsmith Schütze, followed by four generations of the family Zimmerhäckel, also tinsmiths. After 1907, the house was owned by Mr Saitenmacher who gave the name to the “Saitenmacher house”. Mr Saitenmacher produced cartwrights, among other things, sledges. After 1945, the family Schlatter continued to work as cartwrights. Now, the family Kadner runs a flower shop. What a long history. Owning a house is only temporary; someone else will take over later.

Kadner seems to be a common name here. Also the locksmith is called Kadner. Various houses are decorated with frescoes,

It is a charming little city. I follow the narrow streets to reach the train station once more.

Exploring the mountain Geisingberg and the geology of the place

From the train station, I start my ascent to the mountain Geisingberg. I look back to Geising and the mountain Hutberg above it.

Now I am in the forest and look north, where the Ore Mountains level out towards Dresden.

The mountain Geisingberg consists of basalt (Peter Rothe, p. 98). In the beginning of the 20th century, mining basalt started. It was halted in the 1930’s, because the citizens feared that their mountain would totally disappear. The former quarry is now partially filled with water.

On the top of the mountain Geisingberg, I pay one Euro to climb the Louise tower and look down to Geising.

I stand on the tower platform with two muscular men, between 30 and 40 years old. They share their views with me. I wish that the integration of the two parts of Germany would have been smoother.

Walking back down, Geising and its church come closer again.

Friendly and welcoming citizens at the Maibaum Aufrichte (setting up the may pole)

In the late afternoon, I attend the set-up of the Maibaum (may pole) above the city.

While I am eating my pork skewer, the citizens ask me to join them at their table. Soon I sit amidst a group of retired teachers and their pupils, some of them have become teachers now. They wanted to know, whether I have solved all the puzzles about my grandfather. Furthermore, they tell me that I should contact the city historian that has created all he house story panels to learn more about the history of Geising.

With the historian, I make contact later. I might return to Geising to meet him and to find out more about Heribert Fischer-Geising or Ewald Schönberg, the painters that are also related to Geising.

Thank you again

Thank you again, my grandparents, you have taken me to another wonderful corner of Germany that I would have never explored without your direction. My heart is filled with new impressions. I continue my way to Dresden and to Berlin.

Sources: