It is September 2024. After having found two paintings of my grandfather at Neuburg am Inn, I am exploring two more of his works painted at Wasserburg am Inn, about 60km east of Munich.

The first painting of Hermann Radzyk is owned by me, it has no title, no date and no signature. Initially, I assumed that it has been painted in Dalmatia.

The second painting I received from the gallery Dannenberg (Berlin) in spring 2024: “Alte Stadt am Flusslauf” (old city on the river), signed and dated to 1931. The Dannenberg painting clearly shows the same church and fortress as my painting above.

Googling, I looked for the old city with the river and found it: Wasserburg am Inn. Hence both paintings are from Wasserburg am Inn. Probably my painting was also created in 1931. Perhaps, this painting was at the Great Exhibition of Berlin of 1933, with the title “Wasserburg am Inn” (number 309).

Now, early in September 2024, I have booked a room in the friendly hotel Huberwirt am Kellerberg above Wasserburg to look for the locations of the easel.

Easy to find the location of the first painting: The easel stood south of the city and across the Inn on the Uferweg (riverside path). The water front line has not changed much: The balconies and the colours of the houses are largely the same.

This rock looks like a convenient place to put down an easel; perhaps my grandfather’s easel was here.

My grandfather painted the second view from the path leading up to the Kellerberg, but trees hide the view now. This was the best approximation that I could find. I am little too low and a little too much to the left. The house with the chimneys does no longer exist.

The popular “magnificent view” point on the Kellerberg provides a good impression of the city of Wasserburg surrounded by the course of the river Inn, with the church and the castle in the background that my grandfather has painted.

The river had cut a loop into the moraine landscape of Bavaria near Munich. The old city crouches on the resulting half island, 1km long and 400m wide. The fortress protects the land access that is only about 150m wide.

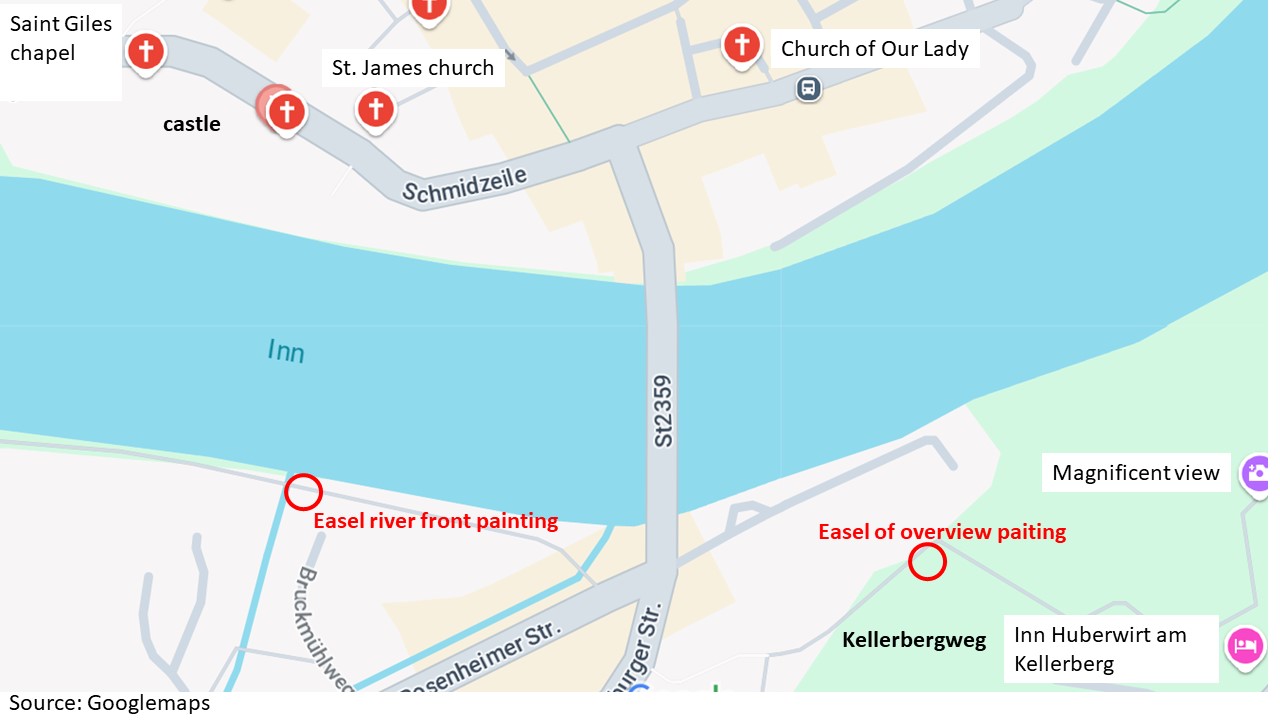

On googlemaps, I have marked the positions of my grandfather’s easel, the first one across the river Inn (“river front painting”) and the second one on the path to the Kellerberg (“overview painting”).

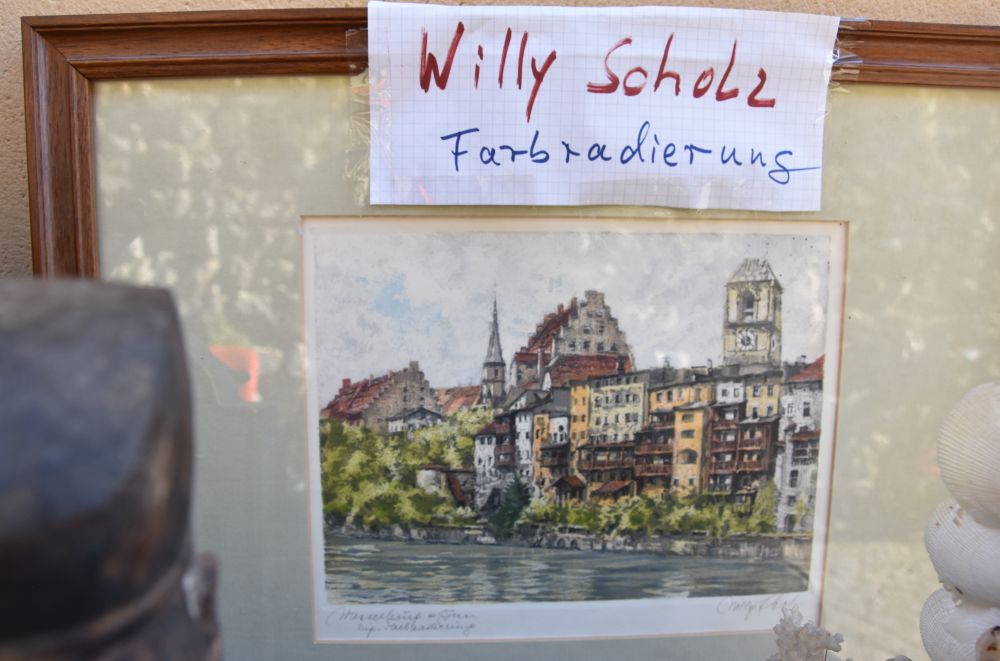

Other painters have liked the river front view as well. For example, I found Willy Scholz on the flee market near the old city cemetery (Altstadtfriedhof).

Mission accomplished – both paintings found. Now let us look at the charming and well preserved city of Wasserburg am Inn that my grandparents took me to.

Exploring the old city center with churches and Town Hall

The medieval city center of Wasserburg has been largely preserved. It was not destroyed in the Second World War. It is a pleasure to stroll through the streets that are less crowded with tourists than other places in Germany. I give a few insights – check the city website to see more of the medieval sights.

After having crossed the river Inn on the bridge below the Kellerberg, I access the city from the south, using the Bridge Gate (Brucktor).

Two guards (Scharwächter) carrying the coats of arms of Bavaria and Wasserburg protect the gate. The fresco was painted in 1890. The artist, Heinrich Georg Dendl, was born at Wasserburg in 1854.

This is the view of the gate from inside the city, from the Bridge Lane (Bruckgasse). The church to the right belongs to the hospital of the Holy Ghost (Heiliggeist Spital). The hospital was active for about 600 years, from the 14th century until 1971.

Mary’s Square (Marienplatz) is the center of the city, with the double arched Town Hall (15th century) and the Church of Our Lady (Frauenkirche; 14th century, inside rococo from 1750).

Across the Town Hall, the building of the noble family Kern (Kernhaus) presents its late early rococo façade from the 18th century that covers two medieval houses one of them being a hotel today.

To the east of Mary’s Square, the Tränkgasse leads towards the former gate “Tränktor”. In front of the gate, horses were fed and watered, as the fresco illustrates (“tränken” means “to give water to animals”) . Horses were needed to pull ships upstream on the river Inn.

Leaving Mary’s Square to the west, I enter the Smith Lane (Schmidzeile) with more medieval houses and with this noble shop selling dirndl dresses.

On the hill, the duke’s castle marks the land access to Wasserburg. It originates from the late 11th century and was acquired by the Bavarian Wittelsbacher family in 1247. The stepped gable is late gothic.

Behind the castle hill, St. James’ Church exceeds the houses of the popular Inn water front line, as we see on the two paintings of my grandfather. The church was first mentioned in 1255 and was reconstructed after a fire in the beginning of the 15th century.

Gothic vaults inside.

The citizens had their reserved seats. Carrier (Spediteur) was a profession in demand at Wasserburg.

The baroque pulpit was created by the brothers Zürn around 1650.

The history of the modest baptismal font is unknown; it could be of gothic origin, but this is not proven.

From the castle hill, there is a nice view of the roofs with the rocks of the Inn loop in the background.

The citizens have set up cosy balconies.

The red tower is part of the city wall.

Under the vaults, I have delicious Bavarian dumplings.

Walking around the city on the river banks

The sculpture path leads along the Inn around the eastern edge of the Wasserburg half island. I enter the path behind the Bridge Gate. Charming small gardens and a great view of the river.

The artists association of Wasserburg am Inn (Arbeitskreis 68) set up the sculptures along the path in the year 1988.

For 135 years up to 1988, the Inn ferry had transported people from Wasserburg across the Inn to the once popular restaurant “zum Blaufeld”. This is, what the explanatory panel says. The restaurant was on the northern side of the river loop that has no bridge.

The convex river bank across consists of rocks covered by forest.

In earlier times, the rocks were not covered by trees. The Inn continued eroding the convex river bank and accumulated the material in front of Wasserburg (this suburbian area is called “Gries”). The construction of hydro power plants along the Inn stopped the erosion and trees started to cover the rocks.

Near the red tower, I enter the city again.

Visiting the museum of the city (Museum Wasserburg)

This is the Herrengasse (“Sirs Street”) running parallel to Mary’s Square. The pink late gothic house hosts the Wasserburg museum (Museum Wasserburg).

I want to learn more about the history of the city and enter.

Two traffic routes crossed at Wasserburg: First the Inn which connected the trade between Italy, Austria and Hungary and second the salt route from Reichenhall (rich in salt) to Swabia and Franconia (lacking salt). Up to the middle of the 19th century, Wasserburg flourished. Trade and shipping created many jobs in the city, such as shipbuilders, skippers, boatmen and carriers, accessories (ropes, chains, anchors etc), loading and unloading, various craftsmen or hospitality. Wasserburg was in addition a naval port, and noble weddings and parties were celebrated on vessels here.

In the middle of the 19th century, the arrival of trains made the Inn shipping route redundant and Wasserburg lost its importance. Now out of focus, the medieval city was luckily preserved in the Second World War.

The collection of music instruments is rich, there are virginals, fortepianos and a large collection of harps.

Old furniture illustrates, how citizens and farmers lived in medieval times – some pieces are gothic.

Workshop setups present old professions such as chandlers.

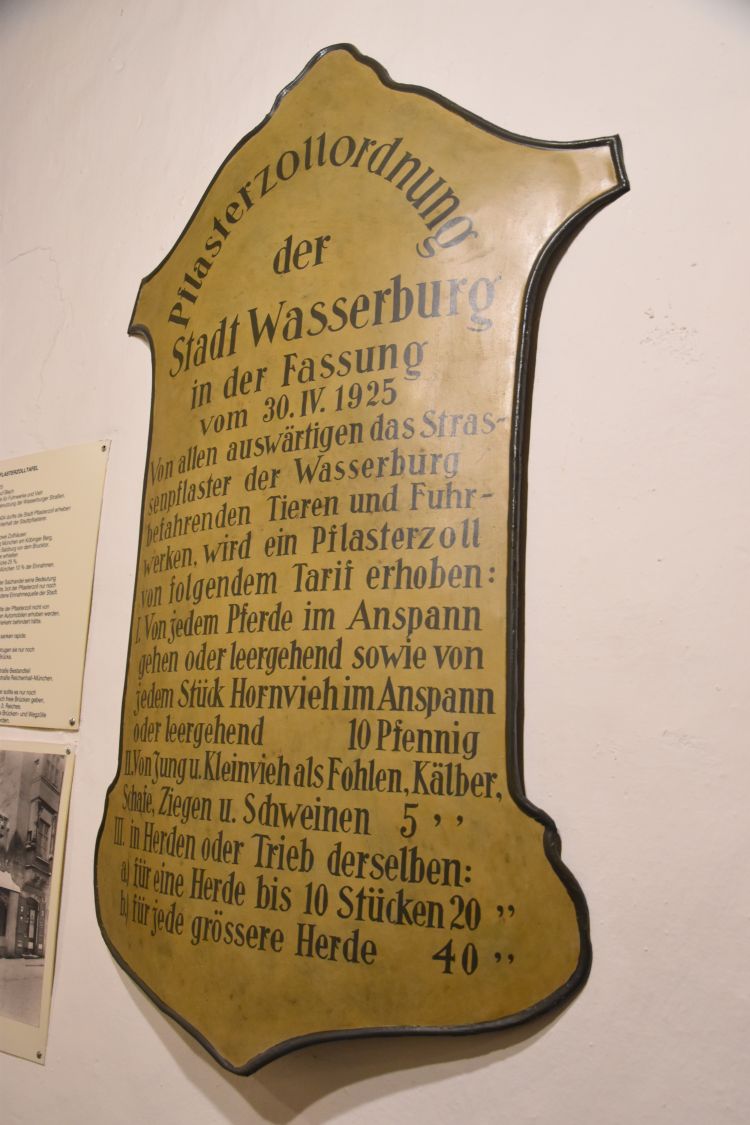

I smile at these “cobble toll” regulations of 1925. A cart with a horse or any other horn cattle was charged 10 Pfennig. Smaller cattle, such as calves, foals or pigs were charged 5 Pfennig. Herds and flocks of them costed up to 4o Pfennig.

Talking about traffic regulations at Wasserburg: I noticed that this medieval city has no pedestrian areas. Cars drive in the streets and are parked all over. Traffic is, however, not abundant. The medieval city on the half island is small. I believe, the people of Wasserburg still live here and want to access their places of living also by car. Its charm has remained a secret uncovered by not too many tourists from abroad.

What a nice city, thank you, my grandparents. The weather changes, and I say good-bye

By his paintings, my grandfather Hermann Radzyk made me visit another beautiful place in Germany. Now I understand, what my mother (his daughter) meant in her diary in the year 1967: She described her thoughts, when she planned our car tour through Germany. She considered including Wasserburg am Inn as being worth a visit, but rejected it, because it did not fit into the itinerary she had prepared. She must have been here with her parents in 1931, then 15 years old. Well, now, in 2024, I was at Wasserburg, and I felt close to my grandparents and their daughter – my mother.

After so many sunny late summer days in Berlin, Poland and Slovakia, the weather changed on Monday, September 9th: Waking up in the morning, I see clouds hang in the moraines around Wasserburg.

Summer is over, and autumn has arrived. I do not feel like travelling in the rain. These clouds look like a lot of rain for a longer period ahead.

I decide to say good-bye to Wasserburg am Inn. I pack my car and about 500 kilometers and some six hours later, I am back at home.

From at home, I observe heavy rainfall hit south Poland, Slovakia and east Austria – I feel sorry for the areas affected by flooding, and I cherish my good travel memories.

Sources:

- https://www.wasserburg.de/de/tourismus-freizeit/wasserburg-erleben/sehenswuerdigkeiten/sehenswuerdigkeiten-altstadt?type=98 (city site with sights overview)

- https://www.historisches-lexikon-wasserburg.de/St._Jakob (for the baptismal font)

- https://arbeitskreis68.de/ (artists association)

- Hans Klinger, “Wasserburg, die Stadt am Inn stellt sich vor”, Wasserburger Verlag, Wasserburg 2005 (history)

- https://www.wasserburg.de/de/startseite (home site of Wasserburg)