In September 2024, I visited Schloss Neuburg am Inn south of Passau. My grandfather Hermann Radzyk painted the castle twice about a hundred years ago.

The first picture has been signed as Hermann Radzig-Radzyk, and it is undated. The painting is in my home.

The second painting, I found in the Internet. It is signed and undated, and has been sold by the Galerie Wildner at Passau.

Hermann Radzyk made these two paintings, when, in July 1925, he stayed in the castle; it was an artists’ hostel then.

For the second painting, the easel stood north-east of the castle. I could reproduce the view; there are just more trees and bushes here today.

For the first painting the easel stood south of the castle near the road. Too much forest here to reproduce the view. On my photo, I stand in the garden above the road. Only here, I could see the defensive tower. Perhaps the easel stood, where the bush below me has grown in the meantime.

Now, let me tell you about my investigations one by one: When I started, I did not know, what castle he had painted. Once I had identified the castle, I looked for the place, where he had put down his easel and for the date, when he has painted it. I will start telling you from the end.

Investigating “when”: No date on the painting – why do I know, the painting is from 1925?

My first guess was that Hermann Radzyk had painted the castle in 1924. In the year 1967, my mother (Hermann’s daughter Marion) took me on a tour through upper Swabia and Bavaria. In her diary she wrote, she was about eight years old, when she stayed at the castle with her parents. While her father painted, she went for excursions with her mother, she added. My mother was born in the year 1916. In 1924, she was eight years old. Hence “painted in 1924” was my first guess.

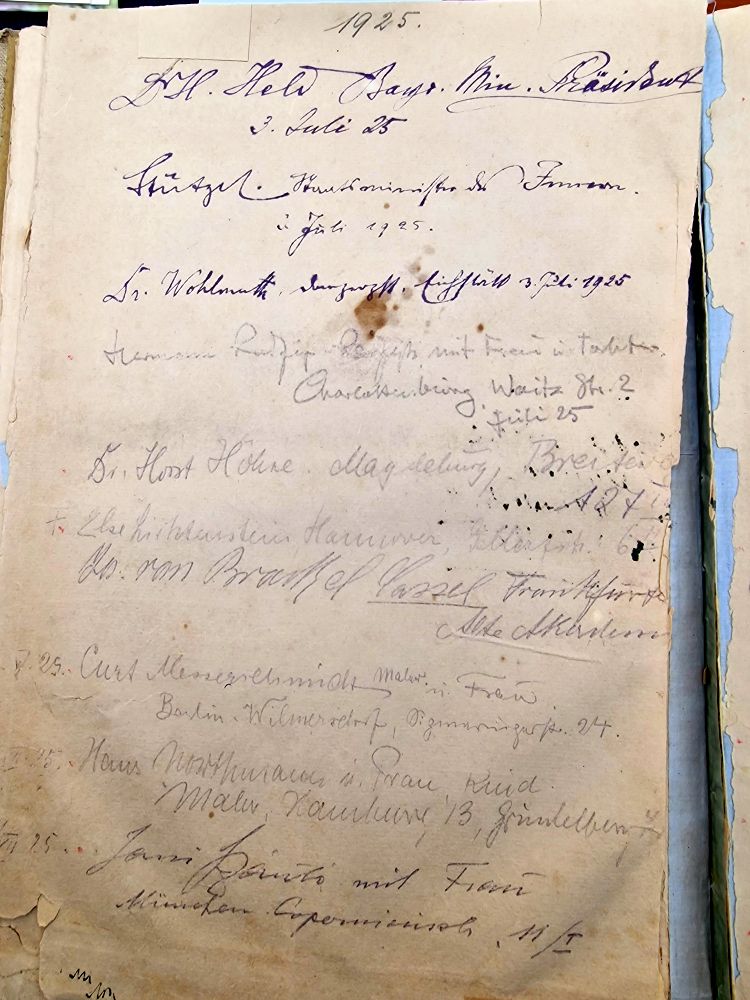

By one year wrong. When I stayed at Neuburg, I found the guest book of the castle, and the guest book told me, the paintings are from 1925.

A friendly man parking his car next to mine gave me the hint: Ask the former Kreisheimatpfleger (the former responsible for fostering regional values). I called and met him in the evening; he brought along the guest book, where I found Hermann Radzyk’s entry not for 1924, but for 1925.

It is the fourth entry on this page: “Hermann Radzyk with wife and daughter, Charlottenburg, Waitzstrasse 2, July 25”.

At the same time, the prime minister of Bavaria, Dr. Heinrich Held, member of the Bavarian Socialist Party, stayed in the castle. Many guests were from Berlin. It was a mixture of politicians and artists. I imagine the discussions in the cosy lounge of the hostel were vivid.

Source: Photo of the castle museum “Landkreisgalerie”.

Surely, Hermann Radzyk painted the castle, when he stayed here in the year 1925. In July 1925, to be more precise. His daughter (my mother) was then 9 years old.

Today the castle offers guest rooms in the former Mälzerei (malting plant). I rented a room here at the same castle, where my grandparents and my mother stayed almost a hundred years ago.

Only double rooms are available at the Mälzerei. I felt like a damsel – well perhaps more like the grandmother of a damsel.

The rooms of the hostel for artists, where my grandparents stayed, were located in the centre of the castle. Today, the former hostel has become the castle museum “Landkreisgalerie”. Access to the museum is via the gallery.

I imagine my grandparents with their daughter walking around the castle to look for a nice view for the paintings.

Investigating the location of the second painting that we can still “see” today

Let us recapitulate the second painting: It shows the north-east side of the castle with the east tower, the defensive tower behind it, and the main buildings with the chapel.

The castle Neuburg stands on a rock above the river Inn. On the northern side, there is a canyon. I climbed up the counter slope and looked at the castle with its entry tower (right), the east tower and, immediately behind it, the defensive tower (called Bergfried or Burgfried in German).

From this view, Hermann Radzyk has extracted the left part with the east tower, the defensive tower closely behind it, and what looks like an oriel is the chapel.

Today, the meadow in front of the castle has mostly disappeared. The son of Lithuanian refugees, who was born in the castle, told me that, in earlier times, when the meadow still existed, it was called “Ledererwiese”, because the tanner spread his leather here to dry it in the sun. No tanner lives in the village under the castle any more, no one needs the meadow now, and the trees and bushes could grow.

On the counter slope, I stand on this small “platform”, the easel must have been behind the bush – but there was no bush here at that time.

I returned in the morning. The light has changed, and it is closer to the atmosphere created by Hermann Radzyk, where the morning sun illuminates the east wall of the castle above the river Inn.

Let us look at the east wall of the castle from the other side of the river Inn, from Wernstein in Austria. We can see the centre castle buildings. This is, where the artists stayed. From the windows and the terrace, they had a wonderful view of the river Inn and the hills of Austria. Now, the museum is to the right of the chapel and the conference rooms are to the left the chapel.

A side remark: My mother was a geologist. In her travel diary of 1967, she described that the river Inn cuts through the rocks of the Bavarian Forest (Bayerischer Wald) and enters the Bohemian Mass (Böhmische Masse), just before joining the Danube at Passau. The canyon is called “Vornbacher Enge”.

Investigating the location of the first painting: Trees hide the view today

Let us recall the view from the south, as captured by my grand-father in the “first” painting.

My mother wrote in her travel diary from 1967 that she immediately recognized the castle, when she drove our car from the south (from Neuhaus am Inn) to Neuburg. She was impressed, how well her father had captured the view and how well he conveyed the impression of the castle. It was engraved in her memory even more than forty years later. We went for a short walk through the castle, and she noticed, it was still a hostel then.

In the year 1957, Karlheinz Biederbick, painted a similar view; his easel was a little lower and more to the right than the easel of my grandfather. Biederbick’s easel stood next to the bus station on the side of the road coming from Neuhaus. This must have been the place, where my mother, 10 years later, recognized the castle, when she drove from Neuhaus to Neuburg in 1967.

I received the photo of Biederbick’s painting from the son of German refugees from Lithuania that were placed in the castle after 1945. He was born in the castle and grew up here. It was still a hostel for artists then, and he grew up with the artists, among them Biederbick. He knew exactly, where the easel was, because as a boy he sat next to the artist.

BUT, when I now, in 2024, drove my car from Neuhaus to Neuburg, I could not see the castle. It was behind trees. I later took this photo from about the place, where Biederbick had put down his easel, next to the bus station. There are some gaps between the trees, where it is possible to get an idea of the defensive tower behind the trees.

Only from the garden of Schärdingerstrasse 28 above the road and above the bus station, I could see the defensive tower. However, the easel of my grandfather stood lower and more to the right. Perhaps where the bush is now. My grandfather and Biederbick could no longer make their paintings today.

The owner of the house 28 was friendly and let me enter his garden.

I met many hospitable citizens at the small village Neuburg grouped around its castle above the Inn. With the son of the refugees (about my age), I spent a warm summer evening in his garden, just under the castle. He lives in a beautifully restored house full of treasures telling stories about the castle and the area around it as well as about his life as a showman with a doctorate in mathematics. It is a welcoming place for a vacation and a great starting point to explore the area at the border between Bavaria and Austria.

Preliminary investigations to identify the castle that Hermann Radzyk had painted

When three years ago, I started the research about my grandfather Hermann Radzyk, I had no idea, which castle he had painted.

I first suspected, the castle was at Silesia. Later I found the castle called Schloss Neuburg an der Kammel in Swabia, but it had only one tower. Burg Neuberg in Austria looked also similar, but the defensive tower had three and not two windows. I knew in the meantime that Hermann Radzyk painted TWO windows, when there WERE TWO windows. Impossible that Burg Neuberg was his castle.

Finally, I thought that perhaps it is not a coincidence that the gallery Windler at Passau has this painting on their website. I looked for castles around Passau, and found Schloss Neuburg am Inn.

This is almost precisely the view of the Wildner painting. The defensive tower in the background has two windows, like on the painting of my grandfather.

I found a different photo of Schloss Neuburg. The “broken” wall looks very similar to the painting that is owned by me.

Source: Landkreis.de

There is just one mismatch: The defensive tower in the middle does not carry a lantern. Perhaps, the lantern has been removed later?

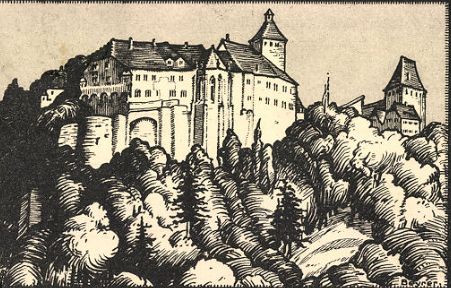

I looked for old postcards. And I found the lantern on the defensive tower.

Source: akpool.de

Now, I was sure that Hermann Radzyk had painted Schloss Neuburg am Inn near Passau.

When, in September 2024, I spent the warm summer evening with the son of the Lithuanian-German refugee, he told me, that the lantern contained a bell and that it was only removed in the 1980’s. This is why, the painting of Biederbick from 1957 still shows the lantern.

Only in summer 2024, I discovered my mother’s diary about our tour in 1967. Only then I understood that I had already been at Schloss Neuburg in 1967, when I was 16 years old, almost sixty years ago. But at that time, I was not aware of the castle painting (it did not hang in my parental home), and I forgot our short visit at the castle. The Baroque city of Schärding and Passau with the different colours of the Danube and the Inn stayed in my mind, but not the castle.

After all my investigations, I added Neuburg to my travel agenda… and arrived here in September 2024 staying overnight at the same castle as my grandparents.

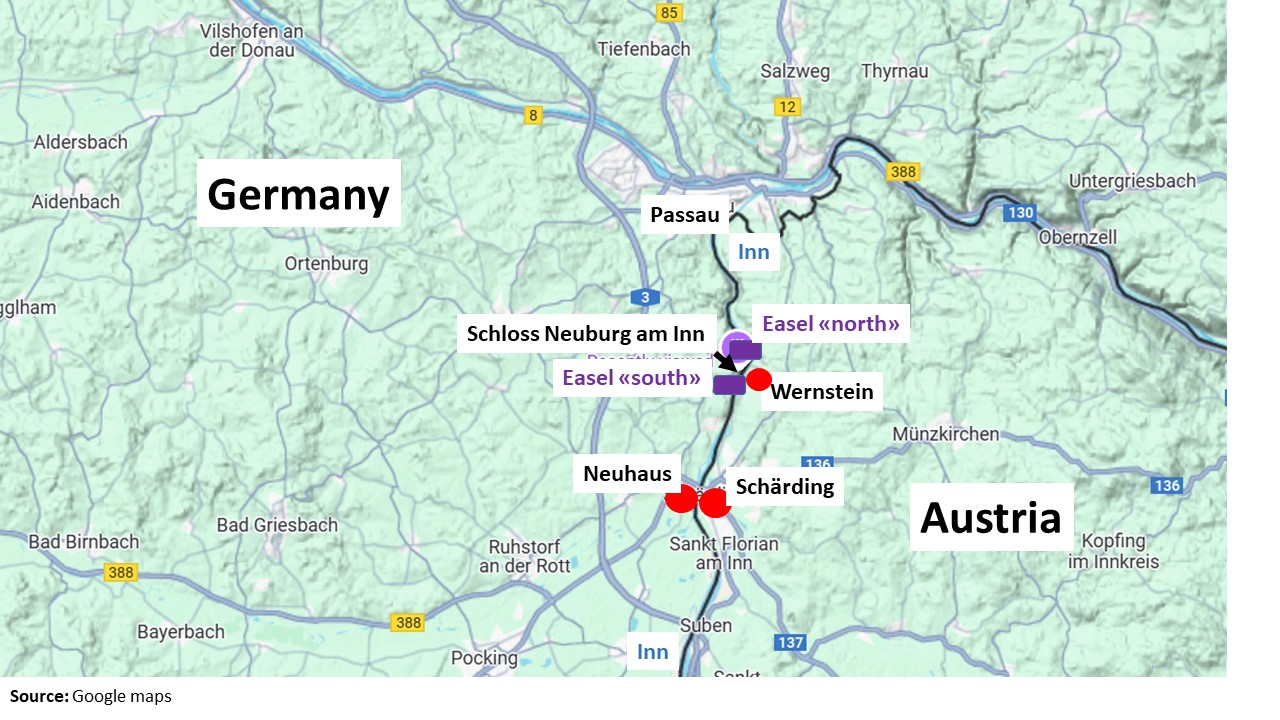

Orientation – where are we?

Schloss Neuburg am Inn is in Germany, above the river Inn. The Inn marks the border between Germany and Austria. Wernstein is in Austria and so is Schärding. Neuhaus, Neuburg and Passau are in Germany.

The easel of the first painting was located near the road coming from Neuhaus (easel “south”). The easel for the second painting was on the counter slope across the canyon north of Schloss Neuburg (easel “north”).

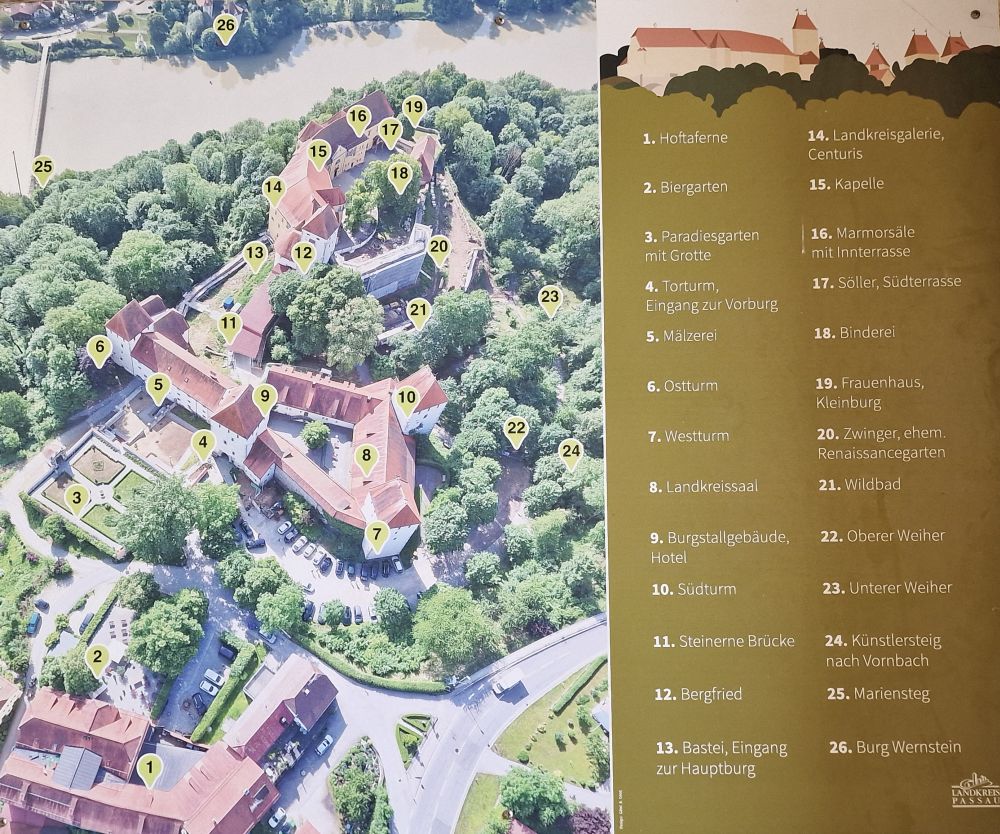

At the entry gate, I found this overview of the castle.

Let us stroll around the castle Schloss Neuburg

Immediately near the castle entry is the paradise garden.

From the fountain in the paradise garden, I am looking towards the entry gate. The Mälzerei is located to the left side of the gate tower.

Entering the gate tower, we reach a bridge that leads to the main tower, the Bergfried in German. It was decorated with the small lantern until the 1980’s.

I visit the museum; it is where the guest rooms of the hostel were before. The cashier takes me to the small chapel behind the museum.

Continuing from the chapel, I reach the painted rooms that now can be rented for events or conferences.

From here, the views of the Inn and Wernstein in Austria are superb.

Strolling around the castle, I find this fairy tale lake. The artists’ path starts here leading down to the river Inn.

The Habsburgian Emperor Leopold I retreated to this castle in 1676, when the Turks became a danger for Vienna (they sieged Vienna then in 1683). At Neuburg, he married his third wife, the Palatine princess Eleonore. It was safer here than at Vienna.

The wooden round panel decorated my room at the guest house Mälzerei, and the Lithuanian-German had another copy of this panel in his house. He made me aware of emperor Leopold.

Good-bye Neuburg

Good-bye Neuburg, I have spent two wonderful days here, I have solved another piece of my puzzle: I found out when and where my grandfather has made the two castle paintings. I have met many friendly people that helped me solve my puzzle here. And I have discovered another place worth visiting, the castle Neuburg am Inn and its surroundings at the border between Bavaria and Austria, with Wernstein, where Alfred Kubin lived and with Schärding that prepared the baroque city centre for the food festival “Schlemmerfest”.

The next piece of my puzzle is waiting for me at Wasserburg am Inn, where my grandfather painted six years later, in the year 1931.